Elective affinities, and other stories

Reflections on recent shows by Richard Thompson and Billy Bragg

I first saw Richard Thompson play when I was 17. It’s an embarassing story. My high-school girlfriend and I had come into Toronto from our smaller town 90 minutes away to see Randy Newman (I was already a huge fan). Thompson was the opener, playing solo I think. We’d never heard of him before—the whole idea of an opening act was probably unfamiliar—and through much of his set we were having some kind of melodramatically tearful teenage fight, causing the adults around us to shush us repeatedly. I shudder to think of it, and I think of it often, particularly when someone at a show is irritating me.

Thankfully the admonitions eventually forced us to pay attention, and at least appreciate the guitar work, as you pretty much have to when Thompson plays “Calvary Cross,” for instance. I soon bought Across a Crowded Room, then his latest, and gradually caught up on his whole timeline, from Fairport Convention through the landmark Richard & Linda Thompson records and beyond.

After that, I didn’t see him again until Oct. 22 this year at the Concert Hall in Toronto. Perhaps the shameful associations had something to do with it. But another part of me has just never been sure I wanted to. As much as I admire RT, and enjoy listening to him in measured doses, I’ve never been quite sure I like him, as a person or at least a persona. I don’t want that to matter. But it does.

We talk a lot these days about “parasocial” relationships between fans and artists—I talk about it here, for instance, in a piece that includes Richard and Linda among its examples of famous musical couples—as well as about “art monsters.” My position is to try as much as possible to view art and artist as distinct. (Not “separate,” since echoes and entanglements are unavoidable.) You shouldn’t mistake artists, much less celebrities, for your friends. And art should not be mistaken for a moral activity. Still, in practice …

I realize that, even if I instinctively side with Linda in the long-ago Thompson v. Thompson imbroglio, that’s the weather, not the landscape. My bigger issue is how, for all their fine derivations from British folk tradition and RT’s undeniable guitar thaumaturgy, so many of his solo songs seem to cast woman as a kind of alien entity. Whether alluring or vexing, sympathetic or spiteful, his lyrical foils seem not wholly people so much as sexualized wraiths and occasions for self-pity. This feels related to the underlying chill I find in most of what are seemingly meant to be passionate songs. (And also to the folk tradition itself, to be fair, but is that the part to hold on to?)

That’s an artistic shortcoming as much as a moral one. But there’s a third thing that it obstructs, somewhere between. Perhaps it’s the sense of affinity, of fellow-feeling, that can make an artist a personal favourite? As a famous art monster once sang, I am human and I need to be loved, just like everybody else. That’s the part that complicates the lines I tried to keep clear and bright above. With Thompson, it just makes me want to shush him after awhile.

There are exceptions, notably what’s become his signature tune for the latest generation of discoverers, the luscious “Beeswing” (it is to the 2020s what “1952 Vincent Black Lightning” was to my cohort). Despite starting from a “lost child … running wild” cliché, in full it approaches being a rounded portrait, framed in a diamantine string cradle. More often there’s a sour aftertaste. Even when I enjoy his albums musically—this year’s Ship to Shore—I haven’t observed much evolution on that level.

This thread of misogyny may be just a subset of a general misanthropy from a loner with shut-in tendencies, perhaps an embittered ex-romantic too. (I think of Joni Mitchell’s “The Last Time I Saw Richard”—”all romantics meet the same fate someday”—though it wasn’t written about RT.) It’s rare outside of those indelible albums with Linda that I find my world enlarged or illuminated by his songs. Their beauty, wit, and sharpness all feel too insular.

That doesn’t stop me from acknowledging Thompson’s artistry, but it’s affected my choices about who to spend several hours staring at in a room. A live show is by nature a sociable occasion. Still, Thompson’s live rep is mighty, and now he is 75. I thought I might regret it if I never saw him again. Maybe I kind of felt I owed him, too, to make up for that first time.

And mostly it was well worth it. I understand full-band tours are rare from RT these days—only in the immediate wake of a new album, so a couple of times a decade. He was joined by spouse Zara Phillips on vocals, old hand Taras Prodaniuk on bass, the precise and forceful Michael Jerome on drums, and RT’s grandson Zak Hobbs—who proved to be his real heir as a guitarist in a way songwriter son Teddy isn’t. (“Nepotism gets you everywhere in this business,” RT joked.)

It was more of a jam show than is my usual wont. Or perhaps cutting contest would be the better term, as RT definitely had to outshine anyone in the band after he’d allowed them to solo. Occasionally his riffing dragged on, but after each lull a dazzle would rise again.

I wished the solo acoustic oasis in the middle had lasted longer—it was only “Beeswing,” but it was extraordinary. As was the acoustic “52 Vincent” in the encore, as well as his game effort at “Cooksferry Queen” (from 1999’s Mock Tudor) in response to a shouted request. The rest of the show he spent mostly on his salmon and red Telecasters and a black Gibson SG, which in one transition slipped from his hands and crashed to the floor—RT had to dispel everyone’s alarm by joking, “It’s fine, it’s only a cheap one.” (It was probably worth nine thousand dollars.)

I enjoyed the 1960s throwbacks such as his long-gone bandmate Sandy Denny’s anti-war “John the Gun” with its four-part harmonies (all too timely this mid-October), and the via-Oysterband-via-Byrds arrangement of “Bells of St. Rhymney” in the encore. And you could feel the freshness of the new songs like the modal “The Old Pack Mule,” which RT intro’d with a vague ramble about Henry VIII, and “Singapore Sadie” in spite of its title and pretty much everything else about the lyrics. The syllables rang out satisfyingly (“burning and blinding and true”) so long as you didn’t listen too close: “Some girls just lay it all there on the table/ She keeps you guessing like Monroe or Grable”—did an adolescent write this? In 1959?

I could have done without RT’s extended discursion on the hilarity of Ship to Shore sounding like “Shit to Shore.” Or his would-be-wry intro of “Tear-Stained Letter” (a song I do love) as “Eighties music, like David Bowie, that glam rock,” and then briefly vamping on “Rebel Rebel,” which is of course Seventies music, as glam was in general, which Thompson apparently missed at the time. Was this man actually invoking David Bowie’s name sarcastically in the year 2024? As I said: Insular, and not the endearing kind, at least to me. A lot of the room was eating it up as if they’d never heard banter before, despite how grey most were (I rarely feel comparatively young at a show anymore). But when you find yourself reviewing the audience, I tell myself, that’s the time to stop. All you can say is you’re experiencing a divergence of affinities.

(Full setlist here, for the curious.)

When Billy Bragg played Massey Hall on Oct. 11, by contrast, I was a fully signed-up cultist. I’m not alone in my age group to stay Bragg’s early albums and interviews played a vital role in politicizing me. As the Clash had done for Billy, he did for some of us. He was also the first relatively well-known artist I ever interviewed, when he played the Student Union building at McGill during my undergrad. There’s a longer, more outrageous story there that I’ll tell you someday over drinks.

There were many more shows, most recently at the Danforth Music Hall eight years ago, when BB and Joe Henry were touring their train-songs album, before which I interviewed him again for Amtrak’s shortlived onboard magazine The National. But it was longer since I’d had the ritual pleasure of a full-on BB solo show, and this was his “Roaring Forty” tour, celebrating four decades since his debut album Life’s a Riot with Spy vs. Spy, as well as his first North American tour. So a certain amount of nostalgic indulgence was in the offing.

I also felt some tension. A few weeks before, I’d had an actual fight about BB with an old friend, one night, after too much wine. A friend who was with me at that show at McGill in 1988, someone I deeply love even when we disagree, but part of a faction of BB’s audience that’s broken away over a series of disputes: the Corbyn-era Labour party, Israel, and trans issues.

Yet at this show I was with a childhood friend whom I’d just converted to BB’s music in the past couple of years, and who was seeing him for the first time. I felt tugged between my two friends’ perspectives, the one beside me and the one far away in both body and spirit, triangulated by my long affinity for that bloke up on stage.

We’re certainly more forgiving to those we feel that way about, aren’t we? In BB’s case, I appreciate that he can still write moving and provocative new songs, even though—like most older songwriters’ work—they’ve become more direct and literal compared to the quicksilver zigzags his writing could take in his youth. More like “St. Swithin’s Day” or “Levi Stubbs’ Tears” are not forthcoming. But I love that he’s still searching and learning, even if some of his revisions of old lyrics are awfully clunky—changing the punchline of his teen love farce “Walk Away Renee,” for instance, from “she cut ’er hair an’ I stopped lovin’ ’er” to “she voted Tory and I stopped lovin’ her,” is borderline criminal. Cheap applause bait.

You might also point to some earlier BB songs as sexist or at least blokeish in the way I was complaining about with RT. In those songs, though, the women still felt warm and alive. BB might be having a stereotypical fight about marriage with “Shirley” in “Greetings to the New Brunette” (as he does in several other songs). But we can see them, vividly, having that long talk on the fire escape, after those evening classes, where her sexual politics have left him “all in a muddle.” Shirley feels like someone you could know. And speaking of “Levi Stubbs’ Tears,” well—RT could never.

BB grew and evolved. He still does. That ability, perhaps that need innate to his character, is also how he gets into political positions that discomfit fans who once traveled alongside him. It’s never without an extraordinary amount of thought. If the spectre of antisemitism in the Labour Party is your concern, for instance, consider how thoroughly he contended with it after he made a statement he felt was misconstrued.

Similarly with trans issues, on which I’m afraid (as this post points out) many of my Gen X peers can sound like echoes of the homophobic older leftists we had no patience for in the eighties and nineties. BB addressed this on stage: “People will come up to me and say, ‘Well, this trans stuff, it’s a difficult one, isn’t it, Bill? It’s tricky.’ And you know what I notice? Inevitably the ones saying it are old geezers like me.”

Frankly there are parts of the highest-profile current trans-activist orthodoxy I can be skeptical about. But I’m pretty confident those things will work themselves out without me. Both for my own well being and everyone else’s, it matters more to keep a leash on my geezerish, change-phobic reactions. That’s one reason I love the song “Mid-Century Modern” from BB’s last album, written during the 2020 Black Lives Matter and other protests, all about maintaining that mental plasticity:

It's hard to get your bearings in a world that doesn't care

Positions I took long ago feel comfy as an old armchair

But the kids that pull the statues down, they challenge me to see

The gap between the man I am and the man I want to be

In the end, friends, if you find yourself aligned with Ron Desantis and against Billy Bragg, I suspect you might be on the wrong side of history.

Enough of the ideological navigations. Those aren’t what I’ll finally remember about this night. Instead I’ll recall the stark anti-war opening, “The Wolf Covers Its Tracks,” BB’s rewrite of Dylan’s “With God On Our Side” (itself a rewrite of Dominic Behan’s “The Patriot Game,” based on the Irish traditional “One Morning in May”). His version is more than 20 years old but feels ripped from Middle East reality right now. I’ll also recall that the hurricanes in Florida and North Carolina were happening right then, and of course there was another BB song fit for the occasion, the climate-themed “King Tide and the Sunny Day Flood”: “Everyone’s a libertarian till the brown water floods their home.”

This is all a part of how BB keeps every gig vital, with his extraordinary awareness of the precise wheres and whens, whether passing along Massey Hall employees’ complaints about not being allowed to unionize the bar staff (the stagehands are organized), or reminiscing about the first times he played Toronto 40 years ago. His brain is a beartrap even in his sixties. He recalled the glorious scuzziness of Larry’s Hideaway (the sex workers from the hotel upstairs used to come “hang around the dressing room and drink my beers”), or the “first and only time” he ever stage dived, at the Masonic Hall (now the Concert Hall), making the mistake in doing so of keeping his guitar plugged in.

He told a funny story about his stop in Vancouver earlier in the month, when he happened to arrive the same night as Johnny Marr and Paul Weller at other venues, as if there were an unofficial UK eighties festival—he played a medley of “Jeane” and “That’s Entertainment” in their honour. When he stopped into a shop there to buy a “shacket” like the one he was wearing this night (his wife tells him they’re slimming), he mentioned he wanted it to wear on stage. The clerk asked who he was. When he gave his name, she replied, “Oh, that’s funny—I think there used to be a singer named Billy Bragg!”

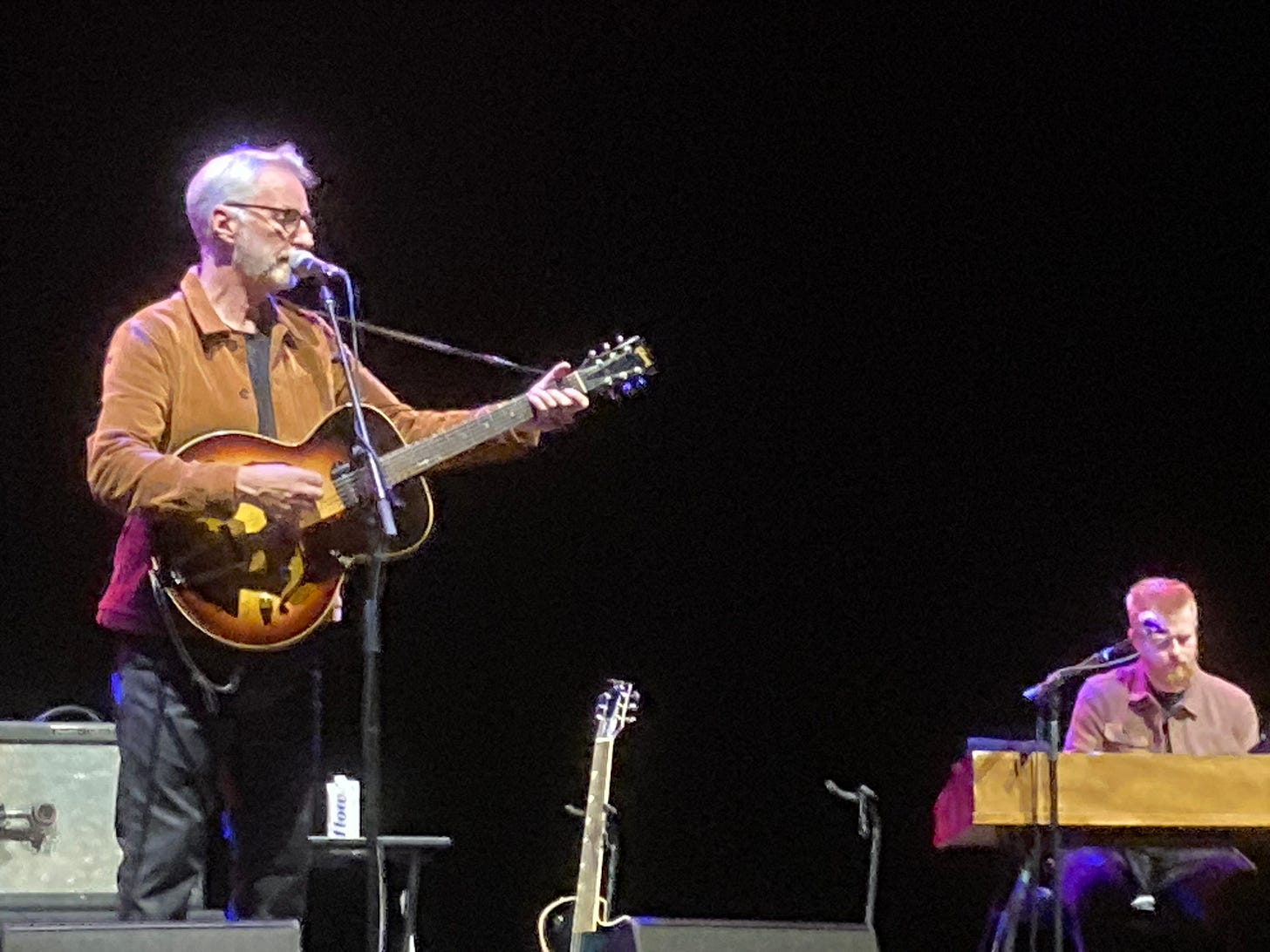

Sometimes on BB’s long disquisitions, his keyboard player JJ Stoney (who entered and exited stage at discreet moments) would do comical background routines to make fun of his long-windedness: at one point he took out a mirror and started pretending to shave; at another point he started swiping a mop across the floor. “JJ’s auditioning for a pantomime when we get back to the UK,” BB cracked.

The freshest twist, though, was when BB turned part of the set into an actual singalong—an acceptance of becoming a “legacy act” I’ve never seen him concede before. He did the thing where he would step back from the mic and let the crowd carry whole sections of the songs on chestnuts like “To Have and Have Not” and (“the only place to go from there”) “A New England.” I joined in full-throatedly and am not ashamed to say I loved it. But I was sad almost no one else sang in my section, an unusually prime spot for press tickets. All the best choruses were coming from the cheaper seats. As usual. (Many of those around me seemed more excited by opener Steven Page. He was okay, okay? I hate the damn Barenaked Ladies, let’s speak no further about it.)

Finally, in the encore, BB addressed the imminent vote south of the border. “There’s a war on empathy going on,” he said, introducing “I Will Be Your Shield.” In the final analysis, he said, “Socialism is just organized compassion. And if it isn’t, you’re doing it wrong.” Whole historical theses could be derived from that. While he admitted music can’t fix the world (“I know at a Billy Bragg show that’s like saying there’s no Santa Claus”), what it can do is diminish cynicism and restore the energies of the people who might make change.

I certainly felt that renewal, or an illusion of it, from joining in Bragg’s congregation. Maybe the closest I get to a faith. I don’t think that boost has weathered the past few weeks all that well, though it flutters back a bit as I tell you about it. Affinity is an elusive thing. An ephemeral ghost of a surly bond. But where are we without it? There is power in a (comm)union.

NB: Yes, this is the first “Crritic!” edition I’ve gotten out in a few weeks. It has been, you may have noticed, a very distracting month. Even more so now, but we desperately need distractions from the distractions, don’t we? So I’m going to try to send out a couple more in the next week, so we can keep each other company. Good luck to us all.

Elegant piece, Carl. I like how you framed Thompson’s relatively narrow powers of characterization, particularly in contrast to his expansive playing. For maybe fifteen years, I’d see him play at every opportunity. He’s in my pantheon (and he was nice to me when I saw him on the street, trotted after him, and asked him to sign a cassette by another artist). But my ambivalence is close to yours. When I saw perform him all the time, I thought his banter was charming but sometimes distancing. He probably didn’t do this every show, but I remember it being routine for him to introduce songs with showbiz irony along the lines of, “Here’s another cheerful ditty.” I understand how that flattered the audience, of course, but I guess it seemed to underline his position as something of a genre writer. I mean, I like genre writers, but it broke the spell a bit when I was young.