For a new Red Wedge (or Black, or any shade of wedge, really)

Seeking collective musical mediations in an emergency

I’m sitting at my kitchen table thinking about Doug Ford and Chappell Roan. Today there’s a provincial election in Ontario, and my vote in a safe NDP riding is depressingly unlikely to help defeat our Trump-Jr.-esque buffoon of a premier of the past seven years. (The midwinter snap election call was timed to catch the opposition off-guard and discourage voter turnout.)

If you live here, I hope you are voting anyway. But here as in the States and beyond, a lot of us have been overwhelmed and dispirited. It’s been a decade of this shit, and the “pussy hat” fight-back feistiness of the early first Trump admin feels far away. Of course there are organizers fighting the good fights, and we should all do what we can to support. But that’s not easy after years of morale being chiseled away by corporatist and other antisocial aggression, not to mention the inevitable sniping and circular firing squads on our own sides, especially online. We know that we share grievances, but seldom feel like members of a commons. I suspect that’s much of what MAGA and its accursed lot have to offer; humans will rationalize a lot in order to belong.

Then I thought about that moment when Chappell Roan spoke out about health care for up-and-coming artists during her acceptance speech at the Grammys a few weeks ago. How exciting it felt for a young artist, in her first peak of visibility, to confront the music-business power brokers right in that room with clear moral demands. Then again, how fast that thrill seemed to evaporate.

To her credit, Roan did follow up by allying with the Backline organization to raise funds. Her gesture also might have helped pressure Universal Music to announce its new joint venture with the Music Health Alliance. But in that high-profile broadcast moment itself, there was no hint that such groups existed—or more broadly ones like the United Musicians and Allied Workers or the Future of Music Coalition, which have been working for years on musicians’ economic and political concerns.

The illusion of everything happening in isolation is fostered by the flimsy linkages of online life. Each of us is the pilot of our own internaut capsule, hurtling through space in a cockpit tagged with our “@” handles, with a field of vision that makes it seem the whole globe is at arm’s length but still untouchable. We have information without form, connectivity without collectivity. Even artistic process has gone that way: The emblematic musical unit of our time is the tandem of solo artist and producer(s), not the musical group. Even what we call a collaboration usually doesn’t involve artists being in the same studio at the same time.

‘The kids are coming in from the cold’

In search of a bit of relief and inspiration, I recently watched two films on the musical-political collectives that sprang up in the U.K. around and after punk: Rubika Shah’s 2019 White Riot, about Rock Against Racism in the 1970s and 1980s, and the much more homespun Red Wedge: Days Like These, an in-the-moment document of a tour of young UK pop and underground stars seeking to defeat Margaret Thatcher in the mid-1980s.

You probably already know something about Rock Against Racism, which was name-checked and imitated around the world for years to come. Punk scenes everywhere had to confront skinheads and other violent racist hooligans drawn to punk’s style and noise. But Shah’s movie gives texture to the haphazard ways the group began and grew.

RAR started almost before punk itself—with a protest letter to one of the British music tabloids after Eric Clapton’s notorious, repulsive anti-immigrant rant at a 1976 Birmingham show. The writers spontaneously added the “Rock Against Racism” name and a post-office-box address to the letter, then suddenly found themselves receiving letters from hundreds of kids across the country wanting to join up. Their imaginary group suddenly had to become a real one. Having access to some printing equipment, they whipped up some badges declaring “LOVE MUSIC HATE RACISM” and a news and music zine called Temporary Hoarding, and before long began booking gigs that pointedly combined white rock and Black reggae bands on the same bills.

Each action led to more young people and musicians joining and organizing local chapters, and RAR became an important pillar of the campaign to defeat the fascist National Front across Britain, among other issues. Their peak probably came with the 1978 march from Trafalgar Square to a carnival in Victoria Park, where the Clash, X-Ray Spex, Steel Pulse, and Tom Robinson Band among others played. (Robinson, now too often forgotten, was a particular luminary of the movement, single-handedly adding homophobia to its list of priorities.) But that was just the most visible of countless events, rallies, and actions. Pretty much directly out of RAR came the often-multiracial bands of 2 Tone (Specials, the Selecter, the Beat, Madness, etc).

In 1982 RAR officially disbanded amid internal tensions about direction, partly for the positive reason that the National Front had dwindled, along with the passing of first-wave punk and divisions among reggae groups over Rasta politics. But over its six years RAR had done a lot to politicize a generation of musicians and fans. That didn’t go away when early-1980s UK music took a cleaner, more commercial turn to new wave and then “the new pop.” Music was still understood to be a counterforce to the reactionary policies of Thatcherism, especially around the 1984-85 Miner’s Strike.

Playing rallies and benefits for the unions led musicians like Paul Weller (the Jam, Style Council) and Billy Bragg to form a temporary coalition with Neil Kinnock’s Labour Party under the banner of the Red Wedge in 1985-86, touring the country to raise youth political awareness and the anti-Thatcher vote. Weller, the most commercially successful of them at the time, subsidized the first tour by providing his tour bus and publicist among other things. On the first major tour, the Style Council and Bragg were joined by the Communards, Junior Giscombe, Lorna Gee, and Jerry Dammers of the Specials, with guest appearances along the way by Robinson, Madness, Sade, Prefab Sprout, Heaven 17, Elvis Costello, the Beat, Lloyd Cole, and even the Smiths. (Yes, sigh, let’s not discuss it.)

Amusingly for those of us who watch a lot of British panel shows, it also featured Phill Jupitus in the persona of Porky the Poet. (In fact one of the Wedge’s later projects was a full-on comedy tour.)

During the days on tour, some of the musicians and politicians would meet with local youth and community groups—the artists stipulated that they weren’t just out to get youth votes for Labour, but to make Labour responsive to youth issues in return. At the gigs at night, they kept the focus on the music, confining the politicians and activists to info tables in the lobby. It was still an awkward fit at times; some politicians disliked the association with artists who wouldn’t hold the party line, while some radical musicians objected to any cooperation at all with a parliamentary party. Labour still lost the next election. But reading Daniel Rachel’s excellent 2017 oral history of RAR, 2 Tone, and Red Wedge, Walls Come Tumbling Down, it doesn’t seem like anyone had major regrets—the heightened awareness and camaraderie were their own rewards.

There was also a continuum between these more radical events and the mainstream: The political consciousness RAR helped make fashionable probably helped lead to Band Aid and the global Live Aid show; those charity events made it more familiar and comfortable to the industry and the media when pop and social causes combined, which in turn fed back into the Miner’s Strike and Red Wedge. Anti-apartheid activism in music (a frequent focus in 2 Tone circles) helped create the conditions for the 1988 Nelson Mandela tribute concert, broadcast to 600 million people worldwide while Mandela was still being imprisoned by the South African apartheid regime. (Further examples followed, from the laudable to the generally ludicrous.)

Here’s a very good Spotify playlist Rachel’s publishers compiled to accompany the book. (Couldn’t find it on any other platforms, sorry.)

The Maple Leaf for-never

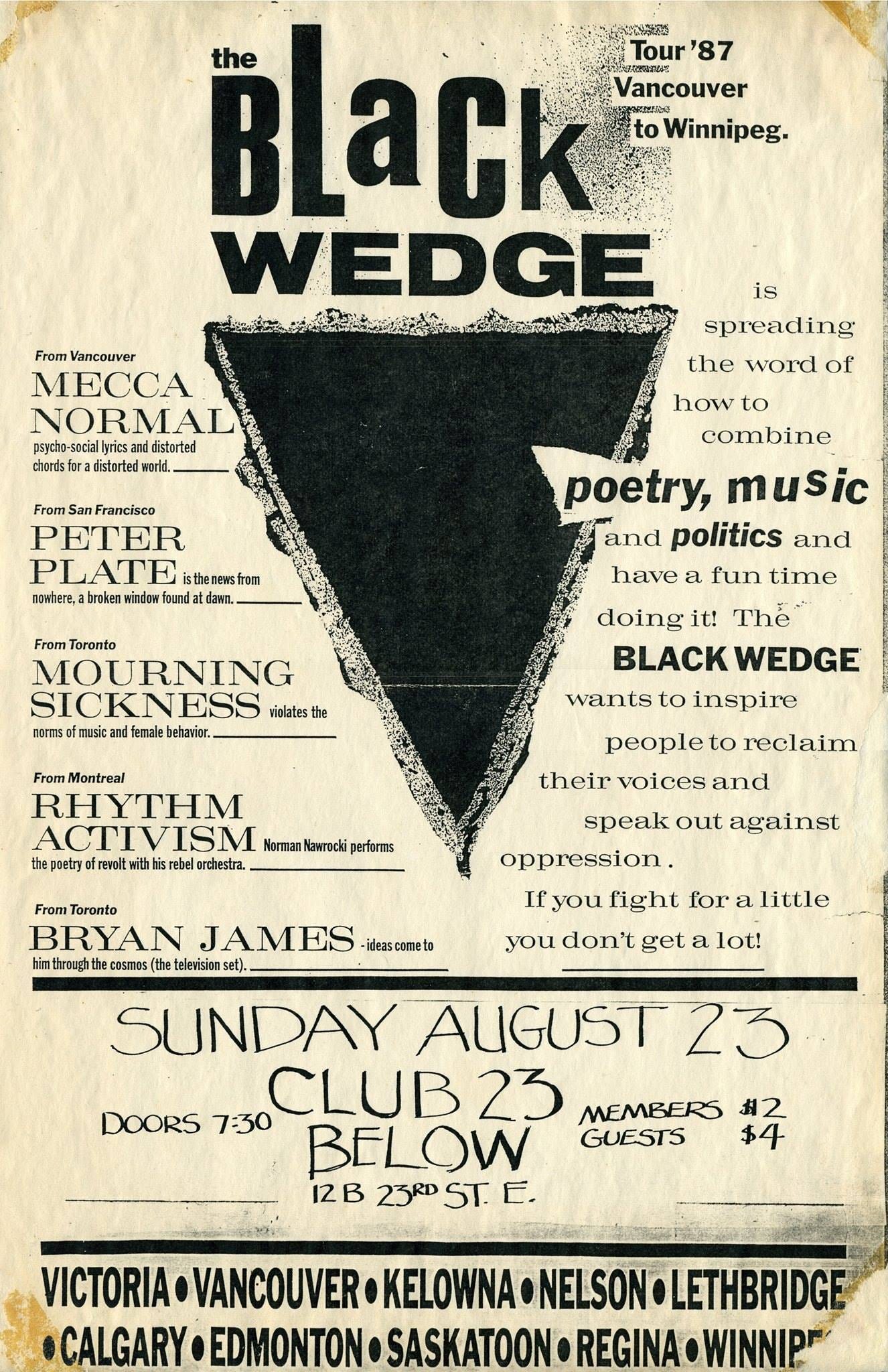

Meanwhile in the Great White North a raised-fistful of politically minded bands picked up the Wedge mantle—but these anti-authoritarian artist-activists were not about to ally with any political party. The core bands on the Black Wedge tour were Vancouver’s Mecca Normal (vocalist Jean Smith and guitarist David Lester, long before they were known as proto-riot-grrl pioneers) and Montreal’s Rhythm Activism (vocalist-violinist Norman Nawrocki and guitarist Sylvain Côté), with a changing roster of guests such as Toronto’s industrial-feminist band Mourning Sickness and various political-punk poets.

There was a 1986 West Coast tour (which was also Mecca Normal’s first road experience) and then at least one subsequent spin through western Canada, and subsequent sojurns that weren’t officially Black Wedge though they were its descendents. On Mecca Normal’s Bandcamp page, Jean Smith says of that first tour: “We borrowed D.O.A.’s school bus and drove the west coast playing clubs, a soup kitchen, an alternative school, radio stations, parties, and the anarchist bookstore in SF. Touring the west coast in 1986 opened our eyes to a whole different underground, a whole new punk rock. Everywhere we visited we met artists, writers, musicians and activists with a DIY aesthetic and their own methods for making things happen.”

You can get the general political tenor from the fact that (as Smith recounted in the 1996 book Sounding Off: Music as Resistance/Rebellion/Revolution (Autonomedia)), she and solo singer Bryan James, respectively the only woman and the only person of colour at that point on the tour, once assembled a zine called Bus Tokens to protest how the white guys on the bus were treating them. Then they distributed it to the audience at their San Francisco show! Which is fantastic and very funny. Given that they all continued on, I assume the white male anarchists more or less accepted the critique as fair game. And I can say first-hand that Smith, Lester, and Nawrocki remain true to their cultural and political convictions in their projects today.

And so … what?

You can’t reproduce the particular coalescence of energies that came out of punk in the late 1970s and through the 1980s. But still, I find these stories galvanizing, of ongoing projects inspiring other ongoing projects again and again over the course of years. They weren’t a one-off protest song or a couple of benefits. They were sustained collaborations between organizers and artists from different communities and at varying levels of success, in flexible coalitions that still had stated names and purposes. They could be mostly bottom-up like Rock Against Racism, or led by star power taking a gamble, like the Red Wedge.

Many artists do some of these things—the likes of Boygenius or Tegan and Sara make space for local activists on tour stops, for instance. But can we imagine Boygenius pulling together several other diverse but similarly-minded acts and doing a six-week tour, say, explicitly focused on reproductive and trans rights? And then following up six months or a year later? Could Chappell Roan get a lollapa-lilith’s worth of other artists on board for a Pinko Pony Club tour with daytime organizing rallies?

You might say the economics make it impossible now compared to the 1980s. Perhaps that’s true, or maybe it just requires some mutual aid and sacrifice. Maybe George Soros could kick in. Or maybe there are other, more 2025-scalable approaches. I’m not the right person to strategize about multi-artist/activist platforms or TikTok accounts. But whatever they are, they should include a real-world aspect, where people can meet in the flesh, give each other the nod, plan a meeting, make out at the bar. Anything to promote a palpable culture of solidarity, to alleviate our loneliness in our faint hopes.

I know political activists are doing some of this. But I’m addressing art and music culture here, where some of us need to draw our oxygen. Is it impossible for artists with profile to get their minds around such prospects now? Is the panicky logic of 21st-century careerism, the gig economy within the gig economy, too all-consuming and tunnel-visioned even to make it thinkable—for anyone to play the Paul Weller role and share the wealth for a few weeks in the name of liberation?

The stumbling blocks are obvious, of misguided do-gooderism on one hand and entertainment-biz colonization and appropriation on the other. I’m embarrassed enough at the naïveté to want to delete this whole post. But that feeling also scares me, that it’s always safer to be too smart to try.

Because if not now, honestly … when?

Thanks for this illuminating — and hopefully somehow galvanizing! — post. You capture our predicament so well with these sentences: “Each of us is the pilot of our own internaut capsule, hurtling through space in a cockpit tagged with our “@” handles, with a field of vision that makes it seem the whole globe is at arm’s length but still untouchable. We have information without form, connectivity without collectivity.”

We belong together. "The manifestation emerges. We face our darkest hour. I turn to music to remember who we are and why we do what we do." https://rickieleejones.substack.com/p/episode-ii-folk-rock-dylan-to-little