To take up arm floaties in a sea of troubles

Seegering and other survival strategies: Keele Life Top 10, Nov 13, 2024

I have been avoiding analyses and postmortems, aka the news. What went wrong are things that have been wrong for years, just at a particular skew. What will be newer and more wrong in the near future we also know. We’re going to need to keep ourselves sane enough to help. Meanwhile in Canada, our version of the worst is still en route. So here are some of the people and things I’ve recently found helpful in the staying-afloat dept., as well as some to miss and mourn.

The mourned here should include Quincy Jones, but I can’t do better there than the one-two of Wesley Morris and Ben Sisario in the Times. Also read Nate Chinen in that same much-maligned venue on the late great Roy Haynes. What lives they led.

1. Rickie Lee Jones,

UB Center for the Arts, Buffalo (Nov. 2, 2024)

Rickie Lee Jones is an artist I’ve written little about, considering how much she means to me. Maybe I fear that if I started writing about Pirates, I would find it too hard to stop. But I felt fortunate to cover her memoir for Bookforum a few years ago. On the weekend before the election, it had been ages since the one previous time I’d seen her live, so I cajoled friends to ferry me cross the border to catch her at U Buffalo’s mall-like Center for the Arts. Jones was a little stilted and shy when she took the stage, alongside her percussionist—perhaps colorist would be the best word—Mike Dillon. But after rapturous reactions to introductory very-oldies “Weasel and the White Boys’ Cool” and “Youngblood,” she warmed. Soon it felt like we could hang out forever.

Jones told us she was turning 70 in a few days (Nov. 8), and that one of the other singers born on that calendar day was Bonnie Raitt (now 75!), which led into a Bette Midler story I won’t hazard to repeat except that it caused Raitt and Rickie Lee to dub themselves “the boob-grabbing girls of November.” She led a singalong through “Love is Gonna Bring Us Back Alive,” and dug deep for obscure spiritual cuts “His Jeweled Floor” from 2009’s Balm in Gilead and the extremely Cohenesque “Altar Boy” from 1993’s Traffic in Paradise. (It begins, “A monk with a hard-on in a lavender robe …”) Our attentiveness there was rewarded with “Chuck E.’s in Love” as well as “Satellites,” then capped with a perfect “Last Chance Texaco.” Yes, she can still hit the high notes, at least when it matters. But even a standing ovation couldn’t bring her back alive for an encore, because she had a hard time limit as the opening act (for Sweet Honey in the Rock, which I’m sorry to report is not the force it once was). I won’t let much time pass before I see her again, in hopes that next time she makes it over to the piano that stood waiting, untouched, all evening.

Meanwhile, RLJ has a Substack of her own called Fish Sticks and you’d be a chump not to sign up.

2. Dry Your Tears to Perfect Your Aim,

Jacob Wren (Book*hug, 2024)

Jacob Wren, from Toronto but long based in Montreal, has been a friendly acquaintance for many years, though I think he suspects me of being a sellout, which is probably healthy for me. (If I have sold out, shouldn’t it pay something?) I really like all of Jacob’s novels, which are threaded with litanies of questions about whether the world can/must change, if art can/should have something to do with that, and how/whether to go on if the answer is no/yes. While their narrators are fictional, they all articulate in an irresistibly quizzical, thinking-out-loud voice that is distinctly Jacob’s. Dry Your Tears to Perfect Your Aim takes wilder leaps as its protagonist crosses the globe to try to join a revolutionary struggle uninvited, wondering whether what he is doing makes sense. Everyone he meets agrees it doesn’t. And yet it seems to be the best he can do.

I was in silent dispute with the narrator through most of the book, and with Jacob about his choices. The geographic setting goes unspecified, avoiding the complications of depicting a real place while risking conjuring up a Generic Non-Western War Zone populated by types instead of people. (In an endnote it’s confirmed to be modeled on the autonomous region of Western Kurdistan, adjacent to Syria, known as Rojava.) I don’t want to give away what ensues, but the plot walks a teetery line between self-aggrandizement and baleful masochism, while alert to the limitations of fiction: Periodic parenthetical asides remind us that the story isn’t true.

So is it a satire of western activists’ mentality around the suffering of faraway others, or is it a case of it? Does it offer a utopianism we need, or a fantasy couched in sophistry? Yes and no, and guilty on all counts. But in risking annoying/offending everyone, like an inverted Houellebecq, its currents of maximal yearning and doubt still agitate the nervous system weeks after reading.

3. Gary Indiana, 1950-2024

Every obit has called him “caustic” or “gimlet-eyed” or even “nasty,” but I just think of him as a good time. Indiana was part of the nest of mid-1980s to early 1990s Village Voice arts writers whose voices collectively made mine, and one of the sharpest stylists of them all, so he soon bailed to write novels instead. The best reminiscences have been the gossipy ones. Christian Lorentzen wrote a fine piece about Indiana’s criticism some years ago. You can read a bunch of his more recent writing on film on the Criterion website. I went digging around the internet to find Indiana with Taylor Mead, Cookie Mueller and others in Michael Auder’s A Coupla White Faggots Sitting Around Talking (1981), which is tedious in the best tedious-art-video sense, and also a postcard from a lost, murdered world. Like everyone else, I reread his Interview dialogue with Chris Kraus, and wondered if the parts about human contact in the past were just nostalgia or also true.

4. Haley Fohr and Bill Nace,

Standard Time, Toronto (Nov. 11, 2024)

This was the first show I’ve seen (though that turned out to be the wrong word) since the election. And it was an apt one, a kind of sonic exorcism. Haley Fohr is the composer-vocalist of Circuit des yeux, a maker of stately mansions of haunting sound and narrative; Bill Nace is a noise-guitar hero who’s collaborated with all kinds of artists, perhaps most famously with Kim Gordon in their duo Body/Head. I wasn’t sure what to expect from their combination. It turned out to be more in Nace’s territory, a suite of drone and aural battery.

The two were seated in chairs a few metres apart at the front of the room. (Standard Time doesn’t have a raised stage.) Nace’s electric guitar was left lying on the floor to generate feedback via sympathetic vibrations, fed through pedals each player manipulated here and there. Meanwhile Nace hammered at the taishōgoto in his lap, a Japanese harp with a keyboard. (Here is video of him playing it solo last year, to similar effect.) He possibly also had a harmonica? Fohr channeled her voice, from grunty mumbles to high howls, via various circuit boxes and electronics at a small table.

That’s as much as I could puzzle out. They performed in near-total darkness, a strategy to concentrate the ear that I actually find more distracting—I spend so much time squinting to discern what those faint figures are doing up there. Still, the shadowy and static spectacle did make high drama of the mere sight of Fohr standing up from her seat and turning to face us halfway through the set. The continuous sound built to quite painful pitches of volume and intensity after that, a heel turn from all-subtlety to all-emergency-sirens. It felt like the audience was being punished, collectively, for some unnamed crime. What it was, I think, deep down each of us knew.

5. Dorothy Allison, 1949-2024

Dorothy Allison, who died this past week, was one of the greatest writers ever about class in America, and her Bastard Out of Carolina is an unforgettable, indispensable novel, as David Cantwell captured in this New Yorker tribute seven years ago. But for something more concentrated, the starter text is “A Question of Class,” and this week in particular, this passage, among many others, jumped out:

Taken to its limits, the myth of the poor would make my family over into union organizers or people broken by the failure of the unions. As far as my family was concerned union organizers, like preachers, were of a different class, suspect and hated however much they might be admired for what they were supposed to be trying to achieve. Nominally Southern Baptist, no one in my family actually paid much attention to preachers, and only little children went to Sunday school. Serious belief in anything—any political ideology, any religious system, or any theory of life's meaning and purpose—was seen as unrealistic.

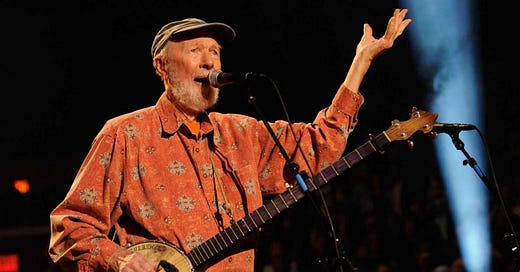

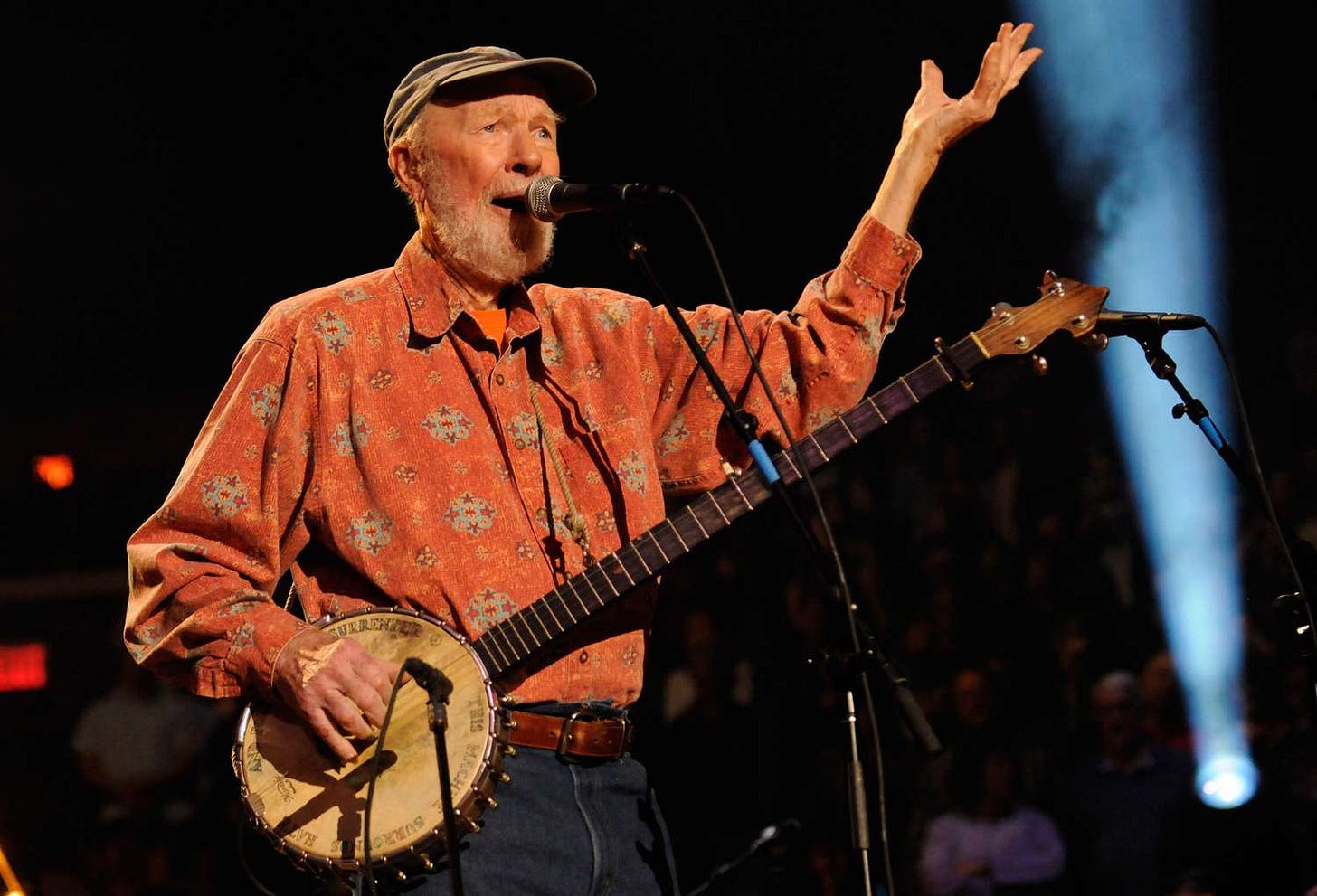

6. The verb ‘to seeger’

Pete Seeger of course was one of the great believers. Also a great teacher whose pedagogical vehicle of choice was the singalong—he would teach a crowd a song (and its message) by quickly speaking the words ahead of the next sung line: “IfIhadahammer/If I had a hammer/I’dhammerinthemorning/ I’d hammer in the mo-or-ning …” I’m sure you recognize the technique I mean. But what’s it called?

I was delighted at an open-stage night at the Mezz in Parkdale last weekend to hear local musician Chris Staig label it “seegering,” while he used it to help us sing Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” I’m going to adopt the term from now on. As in: “Do you know the words, or do you want me to seeger it?”

Lessons for rising dystopias: Naming technologies makes it less likely you’ll lose them.

7. Camelot, Jennifer Castle

(Solstice Radio/Paradise of Bachelors, 2024)

Despite its fairy-tale title, Castle’s sixth album is actually more grounded, its doors wider open, than many of her previous more esoterically minded works. Which are gorgeous in their own rights. But I dare to hope the approach here might attract some new ears to one of Toronto’s stubbornly too-well-kept secrets—call it the Carole King album to her previous Judee Sill-esque ones, in keeping with her 1970s folk-feminist stylistic palette. Also that gymnastics video above for “Lucky #8” slays.

8. Ian Tamblyn, “North Vancouver Island Song” (1986)

(Live in Toronto on Friday, Nov. 15)

Originally from Thunder Bay, Ont., Ian Tamblyn has been part of the Canadian folk scene for more than half a century, part of a generation of poetic songwriters here who searched the land for a national soul, before we despaired of there being one (for settlers, at least). Place him stylistically somewhere between Bruce Cockburn and Stan Rogers, and physically at a lakeside by firelight. I was lucky enough to hear Tamblyn many times on the Ontario folk-festival circuit when I was a teen. Now 76, he’s making one of his rare passes through Toronto on Friday (Nov. 15) at the Free Times. Maybe I’ll see you there. Here is an old favourite, about a kaleidoscopic view through a bus window across Vancouver Island.

9. Céline: Understood podcast (CBC, 2024)

I was one of the interviewees for this new multipart podcast about Céline Dion as cultural phenomenon, hosted by critic and fan Thomas Leblanc with particular attention to how she has conveyed Québec to the rest of the world. Available on all the podcast thingies.

10. Ella Jenkins, 1924-2024;

and Junior Taskmaster (Channel 4, UK)

She stuck around long enough to make it a full century—and to vote for Kamala Harris, I hear. But in the postwar decades, Ella Jenkins arguably did more than anyone to invent what we think of as children’s music now, as both art and activism. She had her own version of Seeger’s technique in fact, a call-and-response structure that owed more to African-American gospel and ringshout traditions, as well as jazzier stuff: She often said she’d been inspired by Cab Calloway on songs like “Hi-De-Ho” and “Minnie the Moocher,” so we could call it jenkensing or callowaying, as you please. I’ve been enlightened on Jenkins’ legacy for some time now by Gayle Wald, whose biography of Jenkins is due in spring; she discussed it in the Popular Music Books in Process series back in 2022.

Less deep in the world of kid stuff, in fact gloriously shallow, is the new spinoff Junior Taskmaster based on the long-running Taskmaster comedy game show on Channel 4 in the UK. The format of Taskmaster is that it takes five comedians per season and subjects them to an array of absurdist “tasks,” such as, “Paint a picture of a horse while riding a horse,” or “Draw the biggest circle,” or “Impress this mayor.” They are then awarded points by the capricious “taskmaster” and ultimately one of them wins the season. It’s sports, but make it ridiculous. (For more on its wonders, read the wonderful Helen Fitzgerald.)

Like much of its North American audience, I began watching obsessively during the pandemic and have carried on ever since—series 18 is just winding up, and it’s all available on YouTube. I’ve even watched the Australian and New Zealand versions. (The U.S. version did not translate and was quickly canceled.) I was a bit skeptical when a kids’ edition was announced, that it might be coy and patronizing, but it has the perfect hosts in taskmaster Rose Matafeo and “assistant” Mike Wozniak, each gently mock-earnest in coaxing and commending or condemning the competitors, aged 9 to 11. It’s also smartly restructured, but frankly the children just seem objectively better on many levels—the tasks were childlike already, and kids are of course better at playing than grownups, at taking silliness seriously.

It airs Fridays in Britain and gets to YouTube on Saturdays. In either adult or kid versions, to disconnect from the darkness without feeling benumbed or stupefied, there’s no brighter beam of lite entertainment.

I grew up with Pete Seeger all around and loved him so much, and also have an awareness it's sometimes a little tricky, from present day perspective, how he gets credited with things invented by people who were't a second-generation Harvard ethnomusicologist.

in that spirit I'd want to point out there are of other names for this thing...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lining_out

https://academic.oup.com/california-scholarship-online/book/28548

"“Lining out,” also called Dr. Watts hymn singing, refers to hymns sung to a limited selection of familiar tunes, intoned a line at a time by a leader and taken up in turn by the congregation. "