Walking contradictions

Partly truths and partly fictions, starring Kris Kristofferson, Jean Arthur, Neko Case, and Josh Johnson on Diddy

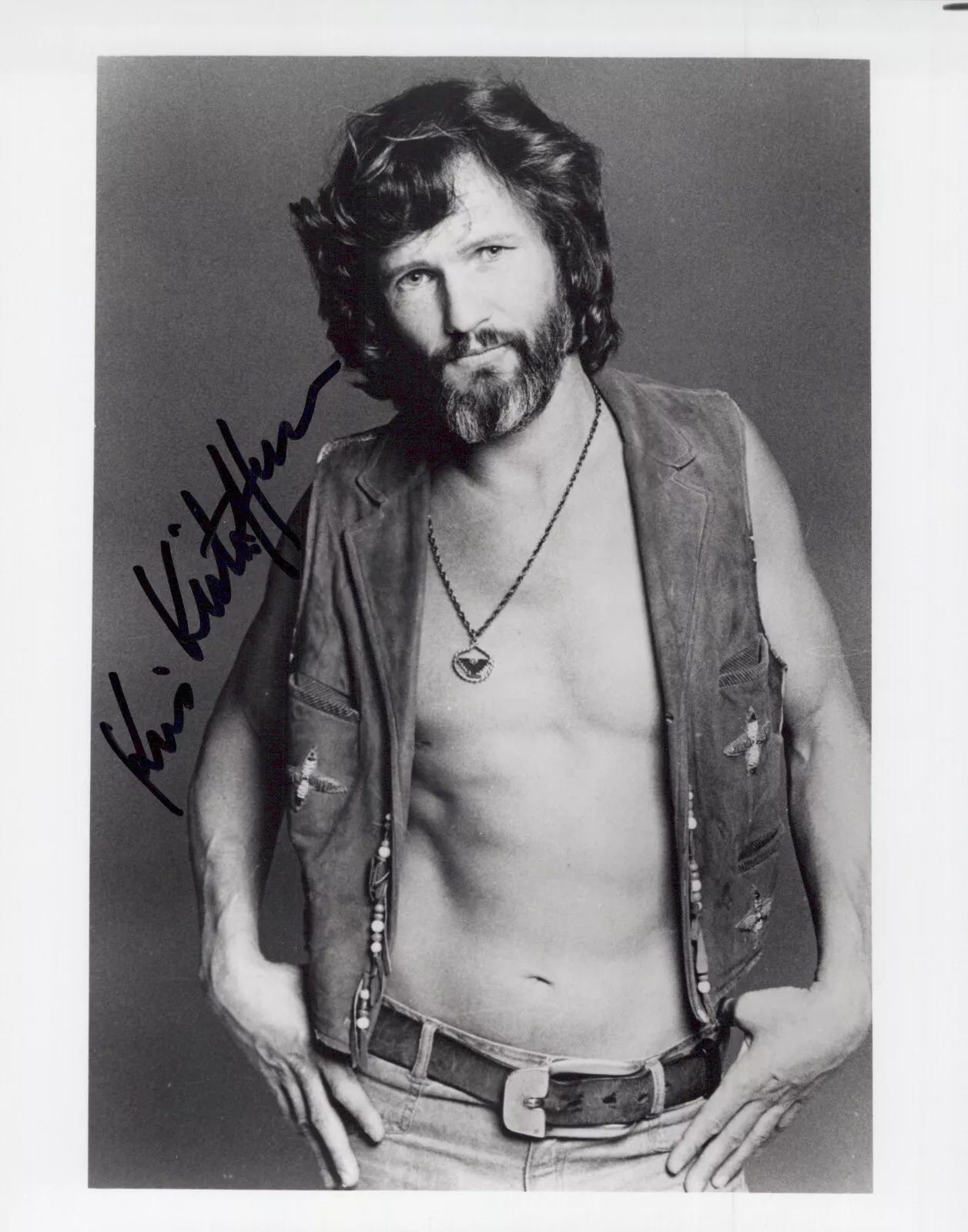

Kris Kristofferson, 1936-2024

Bob Dylan once said that there was Nashville before Kristofferson and there was Nashville after. I’ve been surprised how little of the initial coverage of Kristofferson’s death seems to stress his role in the Outlaw “movement” (as much a moment as a movement)—his stalwart support of Sinead O’Connor in her times of need is fresher on many minds since her death last year, for instance, and fair enough. But he really was the key apostle to carry the counterculture to the citadel of country music, and well beyond countenancing shaggy motorbiker images in those precincts, he brought with him a small but decisive shift in country songwriting.

I mean, damn, the sheer number of astonishing songs. The Dylan-inflected poetics of tunes like “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down,” “Me and Bobby McGee,” “Jesus Was a Carpenter,” and “The Pilgrim, Ch. 33” (the source of my headline and subhed here) may stand out first. But I’m especially struck by the new-generation, tenderly erotic masculinity of songs like “For the Good Times” (which Al Green saw fit to cover on one of his/anyone’s best albums, I’m Still in Love with You), “Lovin’ Her Was Easier,” and “Help Me Make It Through the Night” (Sammi Smith’s version ranked as the greatest country single ever in David Cantwell and Bill Friskics-Warren’s indispensable Heartaches by the Number).

That sensitive-sex-symbol energy, with a twist of the dissolute seer, was what he brought to his sideline as a movie hunk, most obviously in A Star is Born and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. When I get a chance, I’m going to mark his passing by rewatching an old favourite whose memory has faded a bit, Alan Rudolph’s Trouble in Mind, where Kristofferson machinates alongside the equally singular Keith Carradine and Geneviève Bujold, a trio of stray demon-angels. (See Alfred Soto’s writeup.)

Whether on screen or in song, Kristoffer Kristofferson always seemed a little bit like he was on an extended leave of absence from some other life. This was the patrician heritage he carried as the son of a Swedish-American Air Force general. He was born in Texas, reared in California, then went on to Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship, from which he dropped out to join the army, posting to West Germany. It’s not exactly a dirt-farmer country boy’s biography.

No wonder, when he then headed to Tennessee to hang out with Johnny Cash and work his way up as a recording-studio janitor, that his family so vocally disapproved. Score one redemption point for the fairly disparaged art of “slumming.” (He had this in common with oil-family scion Townes Van Zandt, but Townes’ downward mobility was rather more like a plummet from a high tower into hot blacktop.) And Kristofferson did try by turns to use his class-traitor charisma for deserving causes, not just for individuals like Sinead but against, e.g., U.S. policy in Latin America during the Reagan era. I want to go listen to the activist 1980s albums I’ve never heard.

All that stops me, and I don’t think Kristofferson would much mind me saying it, is that as a singer, he was a helluva songwriter and actor. I feel about him the way a lot of people (I’d argue mistakenly) do about Dylan: I would much rather hear almost anyone else sing his songs. Which is no hardship given that the options range from Loretta Lynn to Frank Sinatra, as witness this playlist I found on Spotify.

Living to 88 is no small feat, especially given how hard Kristofferson often lived it. But the circumference of the Earth feels several miles shrunken with him gone.

Jean Arthur and The Talk of the Town (George Stevens, 1942)

A couple of Facebook posts by the writer and scholar Pamela Thurschwell got me going on a mini-Jean Arthur film festival the past month. Though I’m a huge devotee of the 1930s and 1940s rom-com queens—Myrna Loy, Barbara Stanwyck, Carole Lombard, Claudette Colbert, Irene Dunne, Katherine Hepburn of course—I’d always kind of overlooked Arthur. Her superficial winsomeness disguises her intelligence and emotional range. In film after film, her apparent harmlessness serves as camouflage as she crosses class lines and unlooses anarchic social dynamics with the twinkle of an eye.

There she is scandalously sharing an apartment with two men due to wartime housing shortages in The More the Merrier (1943); enabling meek accountant Edward G. Robinson to undo a criminal gang run by the ruthless, er, Edward G. Robinson in The Whole Town’s Talking (1935); helping lead a worker uprising at a department store and converting its Scrooge-like owner to benevolence in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941, not the 1973 Sartre-inspired porn film); or nearly crashing the stock market with what unfolds after an errantly tossed-away fur coat lands in her rambunctious working-class hands in Easy Living (1937).

The Talk of the Town (1942), directed by George Stevens with Cary Grant and Ronald Colman, might be her most subversive romp of all. (Note the similar title to the 1935 film, further tribute to Arthur’s knack for civic disruption.) The plot is almost too convoluted to describe: Grant plays a labour organizer on the lam after busting out of prison, having been framed for burning down a factory in a small New England town; Colman is the idealistically rule-bound dean of Harvard Law who’s come for the summer to work on a book. Schoolteacher Arthur ends up with both under the same roof in her rental property, and has to prevent Colman from finding out that Grant’s not really the gardener, while also fending off both the town’s corrupt police and a mob bent on lynching Grant.

A dizzy domestic idyll ensues in which Colman and Grant play chess and debate legal philosophy (the law is “a gun pointed at somebody's head,” Grant’s character argues; justice “all depends on which end of the gun you’re standing at”) and both seem to fall not only for Arthur but for each other. Never have the stakes been lower over which man a woman in a romantic triangle chooses; Stevens was so unsure that he shot the ending both ways and left the decision up to a poll of test-screening audiences. The answer the movie itself clearly wants is a polycule, in which the throuple carries on their bisexual arcadia in perpetuity, sharing a bowl of borscht “with an egg in it”—a little fertility symbol mixed into your Red Scare. (Both its screenwriters would be blacklisted in the McCarthy era.)

The movie’s charms even granted me a minor synchronicity: Just the previous week on my favourite podcast, No Such Thing as a Fish, the hosts were talking about an early-20th-century kids’ street game in the U.K.: If you spotted someone walking by with a beard, you would cry “beaver!” Turns out they had this game in the U.S. too, because two girls shout “beaver!” at Colman’s goateed professor as he strolls downtown with Arthur in The Talk of the Town. I had to email the Fish crew and tell them.

Neko Case live at the Danforth Music Hall, Sept. 27, ‘24

There were years when I saw Neko Case sing live quite often, at the Horseshoe and sundry places, usually with the Sadies backing her, or even earlier with the group she called Neko Case and her Boyfriends. Later I most often saw her with the New Pornographers. Now, it’s been a long long time.

She still wears her skeleton pants on stage (I forgot Case had been doing this long before Phoebe Bridgers started). She opened with “Maybe Sparrow” from perhaps my favourite album of hers/anyone’s, Fox Confessor Brings the Flood, followed by “I Wish I Was the Moon” from Blacklisted (not to mention True Blood, shoutout to Karen Tongson). At the beginning of that one she hit a bum note, acknowledged with raised brows and a quick sidebar to the crowd. “Do it again!” someone shouted supportively—everyone laughed, but then she did. And somewhere within that relaunched song came the first of many times that my eyes welled up, totally without advance warning.

Crying is pretty far from what New Pornographers shows are about, so I’d forgotten that Case does this to me maybe more than any other singer. It’s partly the distinctive diction and thought patterns of her songs, which aren’t my diction or thought patterns, but which I can fall into like a second language, due to the long familiarity. And is there anyone else who writes so many songs in 3/4 and 6/8? Yet they rarely feel like a waltz exactly, let alone a foxtrot. Much more likely a tarantella or a polonaise. But that’s not just the rhythm of the music, it’s the geometry of how one thought connects to the next.

Those are the six-beat bends around which a scenic description or a mythic tale finds its way to some direct emotional declaration almost too honest and intimate to bear: “I’m so tired.” “They filled me with so many secrets that keep me from loving you.” “I would do anything to see you again.” “Alone, thank God.” She paused during the encore to recall writing that last song, “Hold On, Hold On” in Toronto with the Sadies—“the best song I’ve ever written,” she said. And I choked up again, thinking of course of Dallas Good and feeling sorry/grateful. She also did one cover, of “The Hex” by Catherine Irwin from Louisville/Chicago duo Freakwater, and I appreciated the reminder so much after so many years: Will you know or must I tell you?/ This is my lover's spell you have fallen into/ My dear/ My voice is all you'll hear.

Case’s voice is its own spell, of course. Ringing out danger, justice, freedom and love like that bell in “If I Had a Hammer,” or equally often like a hammer itself, striking anvil. Like a cosmic bat geolocating among the stars. The metaphors accumulate the longer the enchantment lasts. There was a point, I think in “Hell-On,” where I thought I was hearing multi-instrumentalist Adam Schatz squeal a very high note on his saxophone (which he ran through some kind of harmonizer on his keyboard for enveloping multiphonic effects)—but then I looked and saw he wasn’t playing anything. It was all coming out of Neko’s mouth. As she sings in that same song, “My voice is a fracture of a shinbone's lust/ Pounding barefoot ground, it lifts you up/ And sits you just at sorrow's waterline.” The harmonies with singer-guitarist Nora O’Connor were gorgeous too (though I’m always going to miss Kelly Hogan), while Paul Rigby’s guitar was too low in the mix, but que sera sera. When Neko Case is on stage, she is what you’re thinking about.

Unless she directs your attention elsewhere—as she startlingly did when she cussed some idiot out for smoking weed on the club floor, spitting, “You’re going to be smoking that through a fuckin’ hole in your trachea if it’s not put out right now!” (After the next song, she repented her temper a touch: “I don’t have a problem with weed, really. I just want it to be consensual weed, you know?”) And then she ran the beneficent variation a few songs later, pausing and raising the house lights to make sure security came to help someone apparently passing out in the front rows, and warmly acknowledging the nearest bystanders for calling it to her attention.

All of which is to say how present in the moment Case is during a show. Or maybe everywhere, all the time? (She certainly has been when I’ve interviewed her.) Ultimately it’s that unnerving intensity of presence in her songs, the sense of the whole body and spirit being at stake, that makes them so affecting—especially live, in her literal presence.

Case made clear how much she values that experience too, explaining that the album she has coming out next year is partly about “how musicians are going extinct,” and thanking the sold-out audience for doing its part to resist the great die-off of live music. She played three arresting new songs from that upcoming record, just enough to make it hard to wait. It will have been seven years since she last put out an album of new material. In January, meanwhile, she is releasing her memoir, The Harder I Fight the More I Love You. Knowing from songs and interviews some rough outlines of the early life she’s finally prepared here to narrate in greater detail, I’ll say: Brace yourself. The emotional havoc has only begun to be wreaked.

Josh Johnson, “Diddy’s Collapse,” Sept. 25, ‘24

I feel like not enough of us are discussing one of the greatest virtuoso acts unfolding pretty much day to day right now? I suppose the way Josh Johnson’s YouTube channel keeps posting an hour or more each week of standup about current events is not unrelated to the way other stars of the platform post marathon-length videos for followers. But Johnson isn’t just blathering on to offer audiovisual wallpaper and company, the way most of them do. He’s operating at an elevated, precision level of craft.

This week, and this is only for instance, Johnson put out an entire unbroken hour of live standup from Phoenix, solely about the Diddy indictments. He illuminates the horrific absurdities of the situation, combs encyclopedically through the backstory, then philosophizes about the corrupting influence of money and power and fame for the final quarter hour or so. All with jokes. Scripted? Improvised? I can’t say what mixture of the two it is, only that it’s extraordinary, yet basically routine stuff for the 33-year-old comic, somehow juggling this with his Daily Show job, and yet never seeming manic or forced, always laid-back and reflective. I have nothing more profound to offer here than my awe. But if you didn’t know, now you do.

My latest official manifestations

On Katy Perry’s terrible new album for Slate, her possible status as the Shirley Temple of the Obama era, and how she’s kinda like a temporally invasive species in the 2020s.

About romantic couples making music together, and people’s ongoing collective fascination with same, for Arcade: “Musicians are our culture’s appointed philosophers of love; they probe and testify to its force every day on stages and from speakers, and whisper its secrets in our ears via headphones. Actors are just hired hands playing roles, but people want to believe singers are singing their own actual hearts out. And how much more potent if their beloved is right there on the scene of the song to receive and answer the call, the Captain to their Tennille, the Camila Cabello to their Shawn Mendes?”

Me in conversation with Glenn McDonald about his book You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song: How Streaming Changes Music, in last week’s edition of the Popular Music Books in Process series.

Thank you for the excellent movie recommendations, among other great things, this week. I've never seen Trouble in Mind or The Talk of the Town, and now I absolutely have to see both.

In case you're interested, I interviewed Josh Johnson in 2023. He's really impressive. https://www.nola.com/entertainment_life/comedian-josh-johnson-to-perform-at-tipitinas/article_f767caa2-cf38-11ed-ad4d-6b9f30756437.html