“With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do.” - Emerson, “Self Reliance”

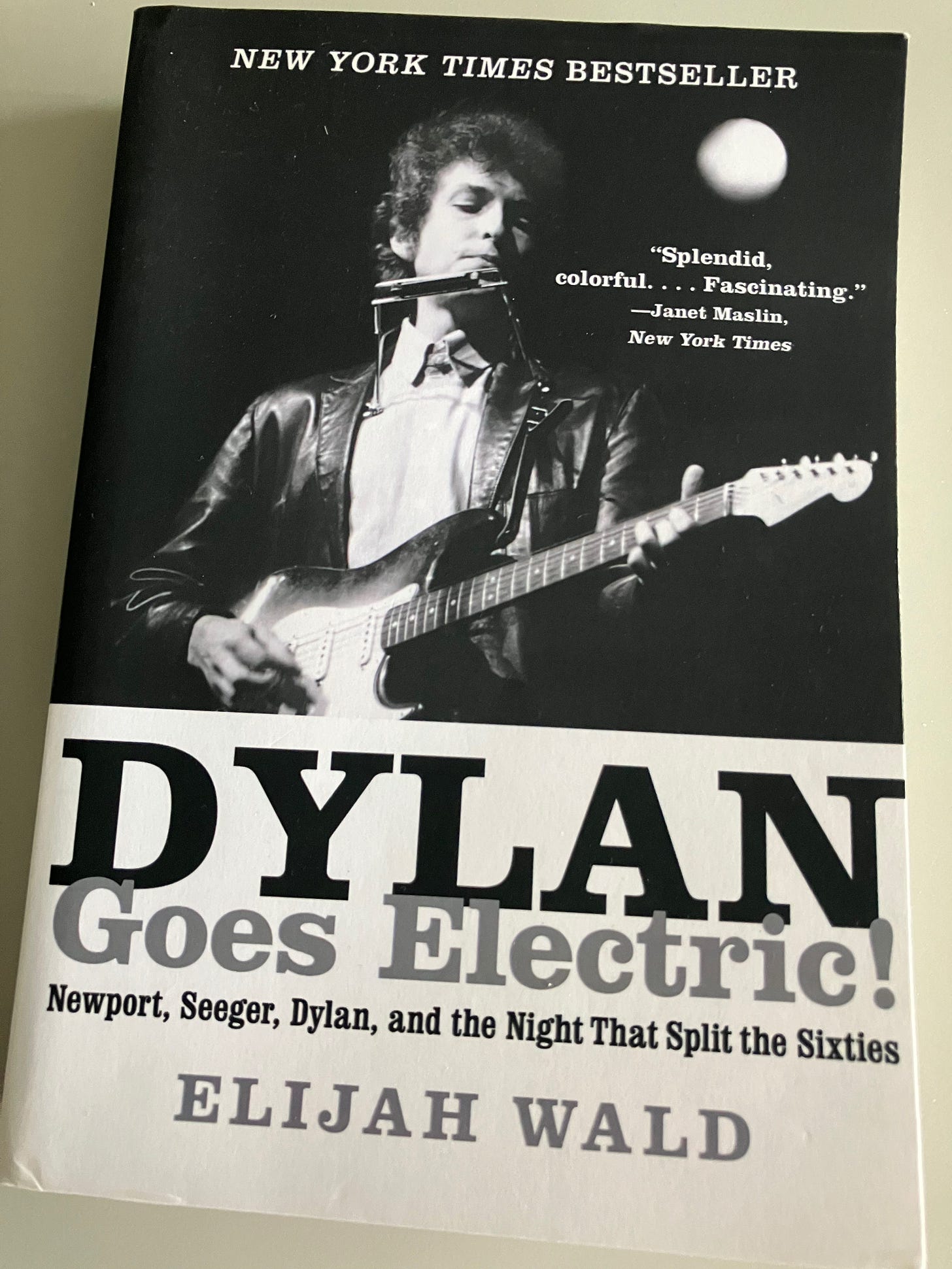

Since Boxing Day I’ve been putting off writing on James Mangold’s Timothée Chalamet-via-Bob-Dylan vehicle A Complete Unknown. I have too much to say, and I don’t want to be one of the nest of nits pecking out petty inaccuracies. The movie’s purportedly based on my Pop Con colleague Elijah Wald’s book Dylan Goes Electric (huzzah to him!), which I reviewed for Slate when it came out in 2015. I have to squint to see the resemblance, but Elijah’s been generous about it. All biopics make distortions, and mostly that’s fine, though I’d say there’s one significant exception here, plus some missed opportunities.

I’d rather watch nearly any mediocre music documentary (and Dylan is a focus of some of the best) than any but the greatest biopic.1 But if you think of A Complete Unknown’s prime audience as being Timothee Chalamet fans, it’s pretty damn good. The Greenwich Village/Newport folk scenes vividly evoked are 60-year-old history—in my own adolescence that would have meant a movie about jazz in the 1920s-30s. (I guess there was Coppola’s The Cotton Club.) There’s a lot of music well-played here, partly thanks to the couple of extra years’ prep time the pandemic afforded Chalamet. The performances are not nearly as stunning as all the staged shots of enraptured crowds strive to convince us. (And not all of Dylan’s early crowds were that enraptured!) But they’re good enough that many viewers will want to hear and know more.

Still, here are my scattered other thoughts. Mostly contrary—this newsletter is called “Crritic!”—but I hope more ideas-based than picayune. From here in I’m assuming either you’ve seen it or you don’t mind so-called spoilers for some of the most exhaustively documented stories in modern music history.

Part of what makes biopics dull and annoying is that the plots are foregone conclusions: tragedy or triumph or first one then the other. Sure, Indiana Jones movies are predictable too, to pluck from another column of Mangold’s résumé: We always know the winner will be Mr. Jones (unlike in a Dylan song, lol). But those movies are full of adrenalizing distractions like huge boulders rolling at the screen, not “and then he played The Times They Are a-Changin’ at Newport and everyone screamed with ecstasy” (which also didn’t happen). The upshot of an Indiana Jones movie is not “… and that guy turned out to be Indiana Jones!”

Like most of the better biopics, this one focuses on a specific period and storyline. But I wonder what young people are making of the whole climax being Dylan playing an electric guitar in public. The first time I saw it, it seemed like the film just irrationally took for granted how dramatic this was. When I went back, I saw that it peppered in more than I’d realized about the folkies’ view of going electric as going commercial and abandoning the political movement, if viewers can figure out what that movement was. The Alan Lomax character even said he had no problem with Black electric blues bands, because they stood in an “authentic” tradition—and in reality those bands had played Newport before, which people forget. But a lot of this is hastily thrown around on screen in ways that would be hard to follow if you weren’t previously familiar. I suspect people are still mostly walking out saying, “Boy, those guys really hated electric guitars. Weird.”

Given both those points, the only way to make the film surprising and exciting would’ve been to play devil’s advocate and slant it hard to the folkies’ side and against Bob’s. As I wrote in my Slate book review, “[Rock] lore holds up the Newport tale as the fierce nonconformist standing up to the timid crowd, but on a deeper level it was one nonconformity against another, a dispute about what it meant to rebel.” A lot of people in 2024 in fact might agree far more with the folkies politically. In crude terms, you could argue Dylan was fighting for his right to be a capitalist cultural appropriator who placed his creative ego ahead of the life-or-death goals of an anti-racist collectivity. If the equivalent of Newport 1965 happened today, the booing would ring across Bluesky.

The movie skips past events like Dylan playing voter-registration rallies in the South, and we only see the March on Washington quickly on a TV screen. If it went deeper into Dylan’s experiences in the political-song movement (relatively brief as they were), had swept us up with him in the thrill of it, it might make real drama of the whiplash changeability of his character and enthusiasms, and make the folkies’ sense of betrayal comprehensible. This movie does let Dylan be an asshole, but not enough of an asshole.

Of course, that script might never have gotten Dylan’s cooperation.That said, personally I don’t care for many of Dylan’s protest songs, while his mid-sixties stuff is crucial to me as the point where avant-garde modernism was first welded to pop-rock, just as bebop had done in jazz a decade-plus before. There were many factors, but the movie way underplays the Beatles’ catalytic agency: Dylan heard them and knew that’s where the action was, on every level. He met them in August, 1964, and by 1965 they were each imitating one another, and there was no turning back. I did love the bit where the Bob Neuwirth character says to the folkie posse something like, “Can’t you see that it might just be more fun to play in a group instead of by himself all the time?” The rest of Dylan’s life really testifies to that.

Dylan is also apocryphally said to have turned the Fab Four on to weed. I doubt it was actually new to them, but he was pretty much always stoned and/or on amphetamines in the time covered by the second half of the movie, which radically altered his writing and his personality. But most of the substance abuse gets put on Johnny Cash, again.

The big factual quibble I do care about, which undermines the movie’s whole concept: What you take away from Elijah’s book is that the Newport 1965 story is large parts myth. Pete Seeger was upset (about the bad sound mix, he said later), but he never tried to get an axe to cut the power cable—that seems to have been a broken-telephone interpretation of Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul, and Mary, who coincidentally died this week) saying on stage “he’s gone to get his axe” when Dylan went to get an acoustic guitar after the electric set. Likewise, nobody threw bottles—he asked if anyone had a harmonica he could borrow, and a bunch of people threw harmonicas up on stage. Yes, some people booed the electric stuff, while some cheered, but the far bigger boos were after the band finished its allotted three songs (there were several more acts scheduled to play), and the crowd demanded Dylan back. But the legend of Newport got enhanced as it spread, and became something people defined themselves around—which famously dogged Dylan through his upcoming UK tour, where booing became a ritual.

This stuff was a revelation when I read Dylan Goes Electric. The inevitable Hollywood decision in A Complete Unknown to “print the legend” feels like it undermines all that work. Aside from a couple of sidelong sops to the truth, it goes all in on the myth of a near-riot at Newport, including the chorus of boos, bottle throwing, Seeger only being stopped from getting a hatchet by his wife Toshi, etc. So that’s going to be jammed even deeper into the collective memory now.Ed Norton’s Pete Seeger might be my favourite performance in the film; he uncannily conveyed the man’s essence. Yes, the film puts Seeger lots of places he wasn’t, but it was a good structural, storytelling decision to set him up as the counterweight to Dylan—Elijah does that in his book too, just without the fibs. However, ahem: Justice for Toshi.2

The clangiest note from the Seeger character is when he tells his (very real) “parable of the teaspoon brigade” to Dylan: About how social movements are like people bringing a teaspoon to fill a leaky basket of sand on one side of a seesaw where the other side holds a basket of rocks—it seems hopeless, but over years, once there are enough people pitching in with their spoons, the balance could suddenly shift. Sweet, but then Movie Seeger tells Movie Dylan that instead of a teaspoon “you brought a shovel” and that if he just plays acoustic that night at Newport, the turnabout could happen now! The “shovel” bit would totally contradict Seeger’s egalitarianism, and I can’t believe he’d ever say something as bone-stupid as the second part.

The movie never really gives a sense of the wider reaction to Dylan—the whole humourless “voice of a generation” poet-prophet-preacher hype that boxed him in so uncomfortably, and the countless imitators popping up. Instead it makes it seem like he was undergoing the equivalent of Beatlemania, with its scenes of girls chasing him through the streets. That was far from the most vexing part of his own peculiar fame. (Notoriously, the most maddening Dylan fanatics are over-earnest dudes who make, uh, lists of bullet points.) Maybe the film doesn’t do so because it’s too busy participating in that same mystification.

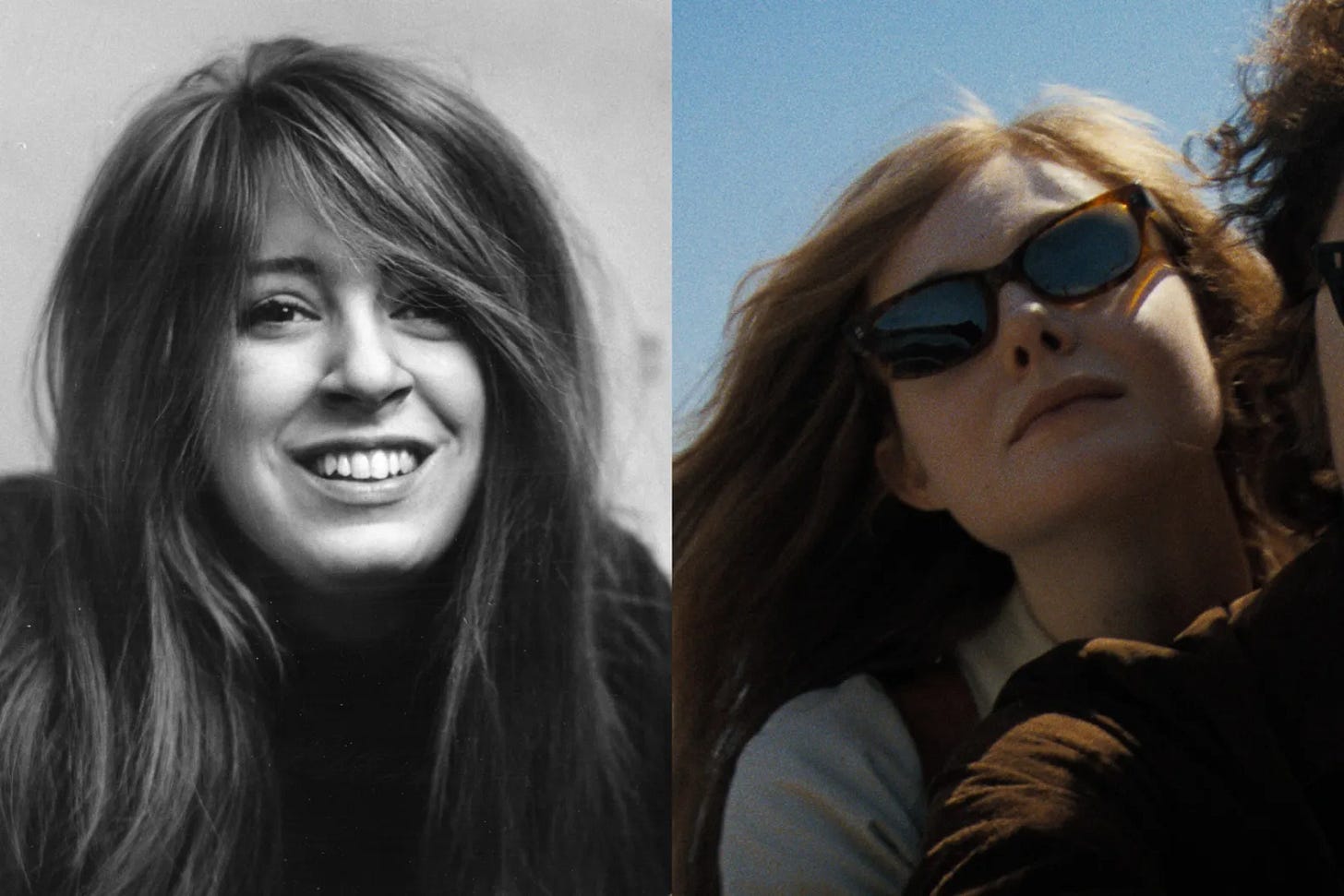

The figure in A Complete Unknown who’s best at conveying Dylan’s whole gestalt via external reactions is Monica Barbaro’s Joan Baez. Partly, it’s musical—though she sounds less like Baez than Chalamet does like Dylan (nobody can really sound like Baez), when they sing together the alchemy elevates the music and the movie beyond any of the solo moments. When she joins him singing “Blowin’ in the Wind” for the first time the morning after their (fictional) first night together, it’s an intimate enough scene about art’s eroticism to require a post-duet smoke. Later they have more or less a musical fist fight just by singing “It Ain’t Me Babe” on stage at each other, and that feels more potent than any of the solo efforts too.

All the better is her sniping at him in the dialogue, which feels exactly true to the Baez we know from interviews. The Sylvie character is constantly hurt by Bobby’s prevarications, while Baez just declares, “You’re so full of shit, Bob.” We know that in reality Dylan hurt Baez deeply in the end. But it feels so right that she gets the upper hand in the fable.Oh, the Sylvie character. This feels like the biggest missed chance. Dylan reportedly asked Mangold et al to change famous Freewheelin’ album-cover girlfriend Suze Rotolo’s name to protect Rotolo’s privacy. Given that Rotolo had already published a memoir about Dylan and done a round of very open media interviews about it, it seems more like he read the script and thought, “That’s not Suze, so don’t call her that.”

The film’s Sylvie (Elle Fanning) is an earnest young student artist-activist fixated on her class schedule and her hurt feelings. The real Suze Rotolo was a “red diaper baby” of Italian Communist immigrants whose household was full of mental illness and chaos, and was as footloose as Dylan. (Her trip to Italy wasn’t a school thing but a family thing, and it was for much of a year, not a few weeks.) Rotolo was way more the real-deal Village bohemian than the con artist from small-town Minnesota was. She was the one exposing him to all kinds of modern art and politics, in a genuinely passionate young meeting of the minds—another case of how the young Dylan threw himself into experiences, rather than just being the perpetual diffident mumbler we see here. When he started writing political songs, he didn’t hide them from Suze as the movie suggests: He had her check them over to see if he’d gotten the facts right. Honestly, a biopic about her would probably have been more interesting than another Dylan movie.Sylvie among others is always complaining in the early parts of A Complete Unknown about Dylan being made to do “covers” instead of his own stuff, which is off-base on so many levels. (This is one point Wald has objected to as well.) Nobody called doing traditional songs “covers”—that’s an imposition of later rock-world language—and when Dylan got to New York he himself was way more interested in nailing down his blues and hillbilly stylings than in asserting himself as a writer. But with some exceptions (like Alan Lomax) most people in the folk scene weren’t against new songs either. Broadside magazine existed just to publish the topical ones, and Pete Seeger was no slouch as a songwriter himself. (“If I Had a Hammer,” “Turn! Turn! Turn!”, “Where Have all the Flowers Gone” …) Plus even when Dylan did turn completely to “originals,” he was still ripping off trad. numbers for melodies and themes. “Maggie’s Farm,” his first electric salvo at Newport, was based on an old tune called “Penny’s Farm.” He never really stopped making folk music.

I do really like the line later, though, in which Movie Bob says that everyone asks him where the songs come from, but they’re not actually interested in that—they mean why didn’t the songs come to them. (Instead of, he might add, this snotty little shit with the nasal voice.) That resentment and bafflement towards Dylan rings true. And it reminds me of the other, better movie based on a book of Elijah’s, the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis, which is based on his book with Dave Van Ronk (who weirdly shows up in this movie as an unnamed side figure always in the middle of an argument about what separates country from folk music). In the Coens’ movie, Llewyn Davis is the guy those Dylan songs didn’t come to, making for an even richer poor-man’s-tour of the Village environs. In Amadeus terms, Davis is the Salieri to Dylan’s Mozart, and as in Amadeus, focusing on that humbler secondary figure is maybe the most profound way of illuminating the unknowable first one. (Plus, Davis is played by Oscar Isaac, a snackable feast next to Chalamet’s canapé.)

I was reminded of the Emerson quote up top by rereading Stanley Cavell’s chapter in Contesting Tears: The Hollywood Melodrama of the Unknown Woman about Now, Voyager — the Bette Davis film Dylan and “Sylvie” go to see early in A Complete Unknown. Elijah Wald has speculated that might have been the made-up scene that Dylan inserted into the screenplay himself, as a vintage film buff. Cavell identifies the film as being mainly about Bette Davis asserting her existential freedom and expressiveness in a society that has no place for it from a woman. I think of Dylan’s Cinderella (another changer of costumes/identities) in “Desolation Row”: " ‘It takes one to know one,’ she smiles/ And puts her hands in her back pockets/ Bette Davis-style.”

More broadly, the implicit subject of many great stars’ performances, Cavell adds, is “their power of privacy, of a knowing unknownness. It is a democratic claim for personal freedom.” Sound familiar, Mr. Zimmerman? Elsewhere Cavell remarks: “Every single description of the self that is true is false, in a word, or a name, ironic. So one may take the subject of the genre of the unknown woman as the irony of human identity as such.”Of course, that’s not this movie. That’s Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There, in which Dylan is incarnated by six different actors, one of them a little Black boy and one of them Cate Blanchett, and none of them called Bob Dylan. I encourage everyone to go see A Complete Unknown, sure, but to get at the bigger truths you need to get loose of the “true story” the way Haynes does. Or to put it another way: To be honest you must live outside the law.

Or sometimes just an unexpected one: I enjoyed the middling Midas Man, the Brian Epstein biopic coming to North American streaming soon, because it’s fun (and sad) to think about Brian Epstein for once and only secondarily the Beatles. Though better still was The Hours and Times, Christopher Münch’s gently suggestive 1991 slash-fic fantasy about Epstein’s 1963 trip to Barcelona with John Lennon.

Thank you for what I personally think is the most insightful piece I have read about the movie. Though I have to say, it is one of those films which, as I harbor serious reservations, I loved. Though I don't disagree with anything you say; it's just that it had an essence I really felt in my gut, a central truth that transcended all of the things it could have done better (though I am offended by the exclusion of Sarah and Van Ronk; Van Ronk, whose pass-throughs in the film were probably anonymous to today's audiences, was a vital factor in Dylan's early NYC survival and he deserves much better).

But yes, it satisfied my desire to see more graphically a part of music history I missed by a few years, yet which was populated by figures I got to know, musically-speaking, well. And it reaffirmed Dylan's position as the great folkie post-modernist. I have always felt a strong ambivalence toward Dylan in general, felt that at a certain point he started to believe in his own genius just a little too firmly; this is something which I think also sunk John Lennon and Lou Reed. If everyone tells you you are a genius than you begin to assume anything you do is a thing of genius. But it's still hard work.

And I have always felt that the Newport performance of Maggie's Farm, whatever the audience reaction, was folk music's Rite of Spring, due in no small part to Mike Bloomfield's musical brilliance.

And at the end of the day I always remember Ed Sanders telling me about seeing Dylan for the first time, in 1963, perform at an anti-Nuke rally. Sanders reported that the crowd was electrified, even at this early point, as everyone knew immediately that this was a new musical phenomenon. I honestly felt that A Complete Unknown captured the strange yet logical path to pop/folk stardom that Dylan represents.

Excellent. I still don't want to see this movie