A Thanksgiving for Jane Siberry

Later Siberry is like later Prince: sometimes maddening, always worth your attention

Last time I saw some shows by long-familiar musicians, I thought about how those experiences are slanted by the differing personal affinities we have with different artists. It came up again tonight seeing Jane Siberry at Hugh’s Room in Toronto, midway through her current rare and brief tour. But here it was about the conflicting affinities we have with different aspects of the same artist.

Siberry has more vastly varied facets than most. She’s among the most original creators from Canada in any field, one of our greatest poets, vocal stylists, music producers, and orchestrators of textures, tints, and feeling. But there are some elements of her work that mean far more to me, while others try my patience. In that sense, it was fitting to see her on the eve of American Thanksgiving, that test of tolerance so many people undergo annually with contentious loved ones. (Especially this year.) It was also apt because whenever I felt restive during tonight’s show, what came next would fill me with gratitude.

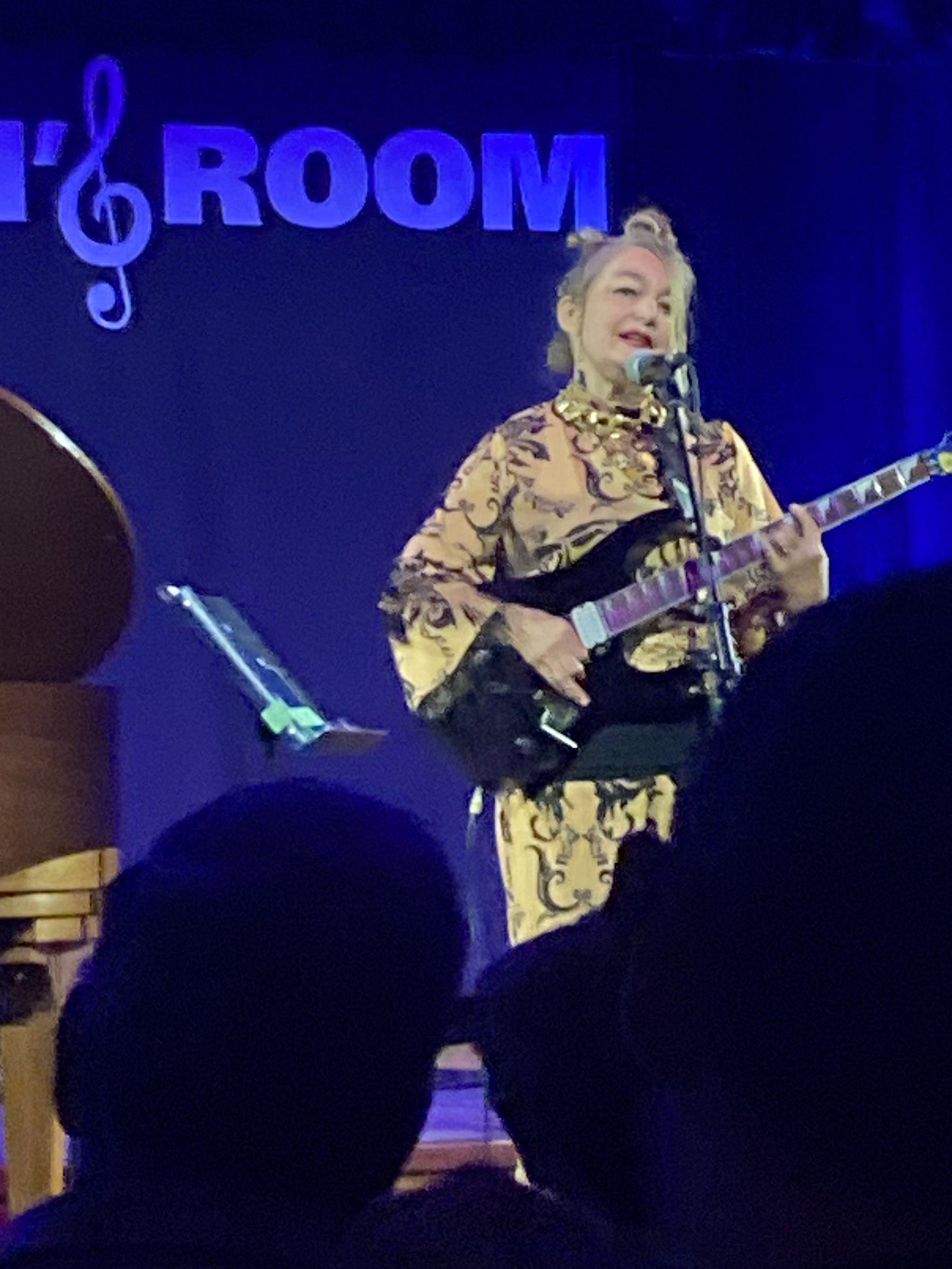

It was my first trip to the “new” Hugh’s Room, a west-end Toronto institution now relocated east to Broadview, into a churchy kind of space rather than a supper club, but still a cozy one. It was packed with people averaging mid-50s, most far more physically fit than me. Jane’s is a very yoga-and-hiking listenership; the lesbian couple beside me were sharing a “sparkling hops water” instead of a beer. Siberry’s godson and his friend opened with a few unremarkable songs that were at least mercifully short—let’s propagate the three-song opening set! Then Herself entered in a gorgeous outfit of yellow chinoiserie, hair swooped this way and that, looking just like Jane Siberry. The arrangement quite, quite there.

I don’t think I’ve seen her completely on her own for a concert before, which focused her on storytelling over sonics. Taking up electric guitar, she set the tone with one of her best yarns, “At the Beginning of Time,” in which a host of as-yet-unformed entities sit bobbing in their vessels on a dark pool, waiting for the world to begin, and murmuring to one another about what it might be like when it comes. (Siberry added some new sections to songs like this and elided others.) Halfway in, when the beings began speculating about what the stars would be like once there were stars, I found myself tearing up. I’m not sure why. It wouldn’t be the last time.

That piece slid directly into the song you might call the Beginning of Jane Siberry Time, 1984’s “Mimi on the Beach,” whose MuchMusic video first brought her to wider attention. It was matched with the later corrective monologue, “Mimi Finally Speaks,” in which the distant woman on the pink surfboard rebukes the original narrator for her mistaken assumptions about her—a debate between two phases of feminism, really.

But if anyone was hoping for a career-spanning variety assortment (perhaps, given the dawning season, some of her sumptuous 1996 Christmas-themed live album Child), there weren’t too many such moments. The encore included “Calling All Angels,” natch, as she tried to entice a reticent Toronto crowd to provide an angel chorus (many of them were in fact not sure how this goes). Before that, she closed the main set with “Morag” from 2016’s neglected jewel Ulysses’ Purse, though it’s not one of my favourites there.

Most memorably for me, midshow, from the piano, we got “Love Is Everything” from 1993’s When I Was a Boy, which pretty much ripped out my hair and left me for dead. I hadn’t heard it in a long time, and I guess it’s been sneaking around following me ever since to observe me and plot its revenge. Just one of the most brutally frank and yet gently hopeful songs around about what love giveth and taketh away.

Otherwise, the evening was taken up with material from her upcoming, fifteenth studio album. Some of it was wonderful, including the very funny “I’ve Never Done Anything Hard,” expressing a distinctly middle-aged mock-exasperation with friends who keep improving rather than indulging themselves as they age (“I’m just a girl who can’t say no to herself”). Introducing the poignant “When You Go,” about choosing how to deal with death and grief, she pointed out the math that if you spend months mourning each person you lose, you could sacrifice most of your own later life in the process.

“Wee Mousie” is a genuinely eccentric amalgam, partly about mercy-drowning a poisoned mouse in a Toronto restaurant toilet, partly about parents awaiting word about their sick children in hospital emergency rooms, with a suggestion that both were metaphors for something more global. It stirred me in spite of itself; in moments of distress now, perhaps I will think of myself as stuck in my chair, “waiting for the doctor’s shoes.”

And “It’s Time to Know Our Name” (another piano piece) offered one of the things Siberry does best, lyrical descriptions of nature, as she evoked the dawn chorus and the drawing-in at dusk—a far more effective way, to me, to summon a sense of spirituality than the sermonizing of “To See Spirit,” which felt like a more rote condemnation of superficiality, and thus a superficial exercise in itself.

I felt similarly about “Atlantis the Sequel,” which muses aloud at exhausting length about revisions of the Ten Commandments that would speak more to modern kinds of soul sickness. And unfortunately also about “Bailout (Ubuntu),” which addresses a topic I care quite a bit about (the cash-bail system and mass incarceration) but more like a by-the-numbers rally speech or editorial than a song. To be fair, Siberry did say that she could only perform “sketch” versions of some of these songs, because the compositions were too complex to play solo live. I know that what’s earthbound in her soliloquizing can be levitated by sound.

Still, these are issues I’ve been having with Siberry for decades. Through the first dozen years of her career, I was swept away by each release, nearly every song, including or especially the ones some might have found too abstract, pretentious, or longwinded, such as The Walking, the 1987 record I’d count among the best Canadian albums ever. (We did feel differently about dogs, but the consensus is that’s my flaw.) But as the 1990s went on there was more of gods and angels, temples and transcendence in her songs than I’d like, and the music lost some of its oblique and sharp angles.

The spiritual-religious stuff bothers me less now, but I still get bored or irritated in the stretches of therapy-speak and moral discoursing on the world’s too many bad things and not enough good ones. There can be a lot of it. It may be what’s on her mind, or what she needs to sustain (or perhaps withstand) her broader visions, but lyrically she no longer troubles all the time to transform the self-help seminars into art. But every release (like Ulysses’ Purse or 2009’s With What Shall I Keep Warm?, all finally on streaming so catch up!) still contains treasures that repay your attention, just as it was on later Prince albums.

In fact Prince feels like the right parallel in so many ways—each of them a universe unto themselves, inconsistent and unreliable but singularly brilliant. They also each morphed in style from release to release, had misfortunes with record companies, and temporarily changed their names: Prince to an androgynous glyph in the mid-nineties, of course, and Siberry in the mid-2000s to the mononym “Issa,” during a phase in which she sold off all her possessions and threatened to quit making music.

I love Siberry now like a dear old friend who has a few pet subjects that wear on your nerves, like the one who goes on about the latest advances in rocket construction, or the other who insists on going on political harangues even when everyone at the table already agrees (or else is never going to, so please pass the cranberry sauce). You shouldn’t love them any less for it. To indulge in a bit of therapeutic talk myself, what you really want to find in yourself is something so expansive you can love them all the more for how you differ, instead of passing judgment.

Siberry made that easier for me in the way she approached the close of her main set, circling back around to the beginning with a wryly imagistic recap of the evening, and then silently playing her guitar to a recorded version of “At the Beginning of Time” that featured a kind of Greek chorus of different voices repeating different lines. It was a sonic evocation of empathy, recalling me to an awareness that the lesbian couple beside me, and the older straight couple a few more rows ahead, and the friend group on my other side, and the people up in the balcony that I didn’t even know was there until the show was over, each had their own long history with Jane’s music and their own reasons for being there, and maybe they loved everything I found offputting and vice-versa.

I wanted to be like the figure in one of the stories Siberry told, who stretched her arms around all of the trees in the forest to become one with the trunks and branches, and when someone asked what she’d do if a grizzly bear came along, said she didn’t want to act in fear, so she would simply try to enjoy the abundance of teeth.

Or like the woman who’s just abandoned her husband or fiancé in “The Lobby,” one of my favourite songs from The Walking that I didn’t dare hope she’d play (and she didn’t), who answers a group howling at her, “This is your darkest hour!” with a very lonely but determined, “This is my finest moment.”

After all maybe the world hasn’t even really gotten started yet, and this is just the waiting room. Keep your eyes peeled for the doctor’s shoes.

Thanks so much. We have been listening to k.d. lang's Hymns of the 49th Parallel since our election here as she animates a loving Canada fron LA to help us imagine a loving USA and Siberry's contribution feels like the center of the album. Only saw her once years ago at the Bottom Line, NYC .

I wasn’t able to get to the show, nor have I been in the new version of Hugh’s Room. However this piece brought me there. I completely agree that her shows can be a mixed bag but I’ve always left them feeling full to the brim and better for it. I’m going listen to The Walking on my drive to Toronto today. It’s also lives in memory as one of my favourite shows…