So here we are for the second time in a couple of days, sitting with the legacy of a crucial architect of musical culture in the 1960s—which, due to a horde of political and technological shifts, is still surprisingly contiguous with our musical culture decades later. Now many of those people are in their 80s and falling fast. It was hard, after Sly Stone and Brian Wilson, not to think, how much longer for Bob Dylan, Stevie Wonder, even Paul McCartney? As I wrote on social media yesterday, it feels like the hearse with the big fins is just revving up to full speed.

I could write at great length about Wilson, especially, within my wheelhouse, about his signature move, which I would define as executing kitsch at such a level that it transcends its kitschiness. In fact the kitsch makes the transcendence better. Wilson’s neurodivergence was part of that: Though I don’t want to armchair diagnose, I think it’s fair to speculate that for one reason or another he wasn’t concerned to distinguish what was kitsch from what wasn’t, via social codes. He was happy to take “surfing, cars, girls” as pretexts for the musical work he wanted to do. He was equally happy to use Tony Asher’s hipster adman poetry (including “God Only Knows,” one of the greatest songs ever written, let alone ever sung by someone with my name). And then there was the Van Dyke Parks bohemian poetry of “Heroes and Villains” and “Surf’s Up”—“columnated ruins domino,” which could again be a slogan for a tipping-over Boomer generation. It’s amazing to hear him do that, but it wouldn’t seem so good if the Beach Boys had not also made “Fun Fun Fun,” which in turn seems better because “Surf’s Up” exists.

In some way that story is also about whiteness. There’s a luxury, a casualness about meaning that Wilson’s peers in Motown and Stax could not afford. Listen to him trying to explain in this interview why he still wants to call 25-year-olds “children.” Even as he says profound things about the theremin. There are famous stories about Wilson’s obsession with “Shortnin’ Bread” as the supposed greatest American song, to the extent that he spent a night in L.A. trying to get Iggy Pop and Alice Cooper to record it with him. But that song was most likely a legacy of minstrelsy, as was the “barbershop” group tradition carried by the Four Freshmen, with whom Wilson was obsessed—spiritual music harmonies squared off by white musicians, becoming a weaker parallel lineage to what would resurface with doo wop. The fact that Wilson had to get sued by Chuck Berry to acknowledge that he’d kinda stolen “Sweet Little Sixteen” for “Surfin’ USA” feels of a piece. (As does the Beatles not getting sued in turn for “Back in the USSR.”) In all these stories, what’s good is also bad and what’s bad is also good.

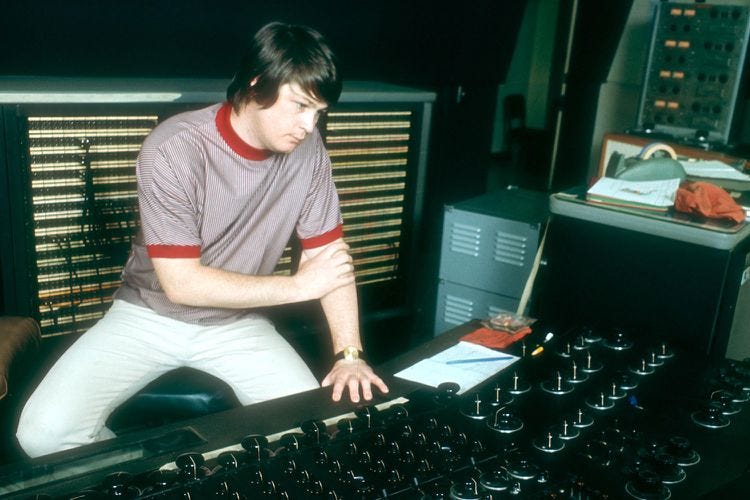

In his unselfconsciousness about these connections, as well as the sudden surges in studio technology, and the year-zero sensibility of postwar California, Wilson was enabled in the early 1960s to reach previously unheard levels of auteurism in popular music creation. I was struck by Ben Sisario’s line in his NYT obituary that “‘Surfer Girl,’ a lilting, harmony-drenched ballad that went to No. 7 in 1963, was perhaps the first pop hit written, arranged, produced and sung by the same person.” Consulting critic friends, and even substituting “performed” for “sung” we could come up with Les Paul and maybe a couple of others who achieved this combination beforehand, but very few. Even Lennon/McCartney and Dylan didn’t reach that level of autonomous self-determination in the studio anywhere near those years. (Although Wilson also was not as independent of the rest of the Beach Boys as people tend to think.) After Wilson there was Stone, another California kid, and eventually many more—Prince top on the list—but he was a true fount of that evolution.

Wilson is also one of the examples one could invoke to object to Questlove’s proposition in Sly Lives! that Black geniuses are tested and punished for the burden of their gifts, while their white equivalents go on living comfortably. Still, all of Wilson’s drug dependency, crashouts, ripoffs, and life of abuse by supposed caregivers still had nowhere near the comparable consequences as for Stone—who became broke, homeless, and repeatedly incarcerated. In the paradigm that Jonathan Bogart described as "one-time symbol of bravura youth culture, trapped for decades by the fallout of the sixties, who fought free and became a widely beloved elder,” both deaths hit hard. But Sly, for instance, never had the equivalent of the Wondermints to help him recreate and redeem his lost works. His period of senior freedom and belovedness was much briefer than Brian’s.

Wilson’s death also makes me think of another kindred spirit, the late David Thomas of Pere Ubu, whose love for Wilson (and the aforementioned Van Dyke Parks) was actually what pushed me to reassess the Beach Boys in my 20s—after a youth spent, like many of my peers, rejecting them due to the post-Endless Summer onslaught of Boomer nostalgia marketing. Thomas looked at the then-”lost” album Smile as the ultimate achievement in popular culture, in its own way—asserting that what listeners imagined or reconstructed (across various bootlegs, for instance) about a work never released would always be greater than any existing work possibly could be. You might compare it to unrequited love’s pure intensity compared to the mundane complications of lived relationships. In some ways the later finished Smile (with the Wondermints) proved Thomas right. As did the official complete releases of the Basement Tapes recordings by the Band and Bob Dylan, which could never equal Greil Marcus’s descriptions and interpretations in Invisible Republic (aka The Old Weird America). O lost masterpieces, stay lost.

Thomas also took Wilson as a model of how to sing about America—about the mythos of its consumer-culture symbols in tension and contrast to the geographic and geological undertext: land, road, sea, electricity.

Another thought that Sisario’s obit sparked is that songs like “In My Room,” “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times,” “God Only Knows,” and other anthems of Wilson’s more sincere downbeat emotions are probably the ones young people today have heard most. It’s the opposite of how Gen X and millennials first encountered them—in the 21st century the revelation might be, “Did you know that guy who wrote those delicate ballads of introversion and depression also wrote hits about surfing?”

Finally, yeah, Mike Love’s probably a dick but he also got ripped off of credits as a lyric writer for a long time until he went to court (he wrote the words to “Good Vibrations” among many many others). And he seems to have had a sincere love and friendship for Brian. So reserve more of your vitriol for his uncle, the Wilson brothers’ dad Murray, that battering and mismanaging old bastard who probably struck the blow that half-deafened Brian. Imagine Wilson with any more sonic perception he had. Every extra decibel could have changed music history.

Tonight I was imagining David Thomas lining up behind Dennis and Carl Wilson to give Brian a huge bearhug in the afterlife, if there were one. While Sly Stone looked on, suspiciously, sidewise. And these Thomas performances of “Surfer Girl” and “Surf’s Up” (far from accidental choices) would be sounding from the celestial jukebox.

Love and Mercy to you.