“I call ‘monster’ every original inexhaustible beauty.”

— Alfred Jarry, author of Ubu Roi

It took three tries for death to get David Thomas, the singer, poet, theorist, and provocateur of Pere Ubu. He’d technically perished twice in his decade-plus of dealing with kidney disease, before his actual death Wednesday, April 23 (also Shakespeare’s death day, just saying), in his adopted home of Brighton and Hove, England. His wife Kiersty Boon’s announcement said his body would ultimately be returned to his family’s farm in Pennsylvania where, with his usual brutal irreverence, he insisted he be “thrown in the barn.” He was only 71, but news of his health scares have been rippling out among fans for at least a decade and a half, while he kept drinking and smoking (he quit cigarettes for vapes only in the last year). So lasting even this long was its own triumph—not unlike the persistence of Thomas’s music career across six decades despite being by most measures completely non-viable.

Here was a corpulent, professedly tone-deaf intellectual (though he’d sneer at that word) from the “wasteland” of 1970s Cleveland, given to cursing and sputtering at his audiences and bandmates, writing abstract poems delivered in wheedling mewls and often incomprehensible squawks over spacey analog-synth noises, sometimes while banging an anvil or blowing into a toy horn, declaring that he was the true bearer of the main line of rock music, next to whom the Eagles or Van Halen were far-out aberrations. A joke, yes, but one he also believed, which was his general modus operandi.

After his first attempt at making a band in 1974 with Rocket from the Tombs sputtered out in months, Thomas seems to have resolved never to let that happen again, and only his death prevents Pere Ubu from reaching its 50th anniversary this summer. (Though Rocket also reunited for shows and recordings in the 2000s and 2010s, see below.)

Yes, Ubu has gone through 20 or so band members along the way, with Thomas the only constant, but it was not a Mark E. Smith situation: Many of those members stuck with it for a dozen or more years while juggling other jobs, or repeatedly left and returned, for rewards that must have been personal and artistic because they certainly weren’t financial. Few of them have kvetched about Thomas in public, though no doubt he’d deserve it.1 (I loved this reminiscence on Bluesky by a former member of his management team, which shows both sides of the coin.)

Thomas identified with Orson Welles—not only was there an uncanny physical resemblance but both were stubborn prodigies heralded and rejected in their fields almost in the same breath, who had to sustain the rest of their artistic existence on their wiles. The final Pere Ubu album, which he’d been working on till the end, sometimes from his hospital bed, is called Chimes at Midnight; in 2013, they called one Lady from Shanghai.

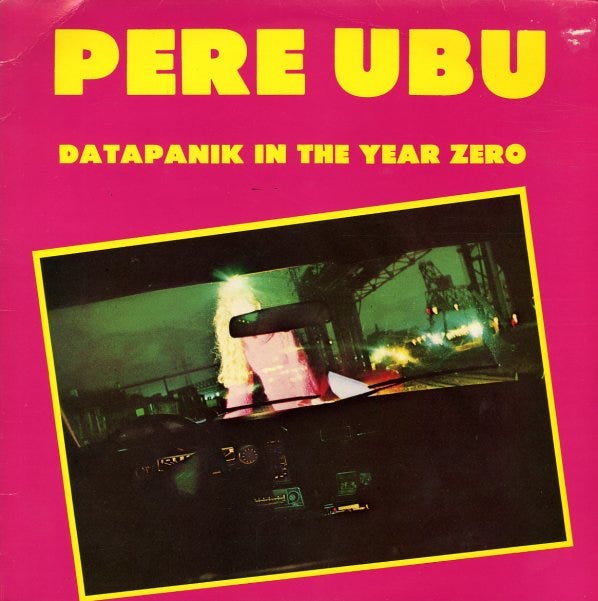

No matter how absurd his convictions, Thomas could half-persuade you he was right with his speed of mind and charismatic force. Many people thought he named the band because of his own resemblance to the rotund, ranting King Shit from French symbolist Alfred Jarry’s 1896 play, but it was actually because even as a teen he was excited by Jarry’s stage techniques (e.g., no scenery, just placards reading “a forest” or “a bedroom”) and his philosophy of ‘pataphysics, the “science of imaginary solutions.” Thomas remained a ’pataphysician extraordinaire to the end, offering in song, stage banter, writings, and interviews his inside-out answers to genuine world problems—such as “datapanik,” the condition of being so flooded with information that truth disappears, which he began talking about in the 1970s—as well as to his own self-inflicted dilemmas.

In a live staged interview in England a decade ago, he began by warning his interlocutor, “There have been a lot of girlfriends, over the many decades, who always end up leaving me, because I don’t, I just”—here he paused and made a sound like uhhhhhaaaaaaaaaiiiiiaaah, heightening the tension and setting up the punchline—“don’t need your input.” You certainly could count Thomas among the great bards of the non-neurotypical, but such categorizations are too dull a tool with which to treat this man who was absolutely one of one.

Still his use of his love life there to make the point struck me. One thing that’s often lost in the mythos about the Cleveland industrial landscape and musique concrète and other critical clichés (all also true) is that Thomas is a deeply romantic writer, though by no means a sentimental one. The frustrated yearnings of estranged lovers are as present in his work as the spooky entanglements hidden beneath the American surface, both natural and cultural. As well as, you know, ducks and dinosaurs and radios and stuff.

One of my favourite records is a solo album called Monster Walks the Winter Lake. It begins with improvisational light looseness with a mostly acoustic ensemble (plus Allen Ravenstine’s EML synths) but gradually draws to the titular centerpiece, an eleven-minute sidelong portrait of a marriage in crisis that has generated its own simulacrum, a charming but hollow, lumbering “monster” that he pictures poised at the lip of half-frozen Lake Eerie, “the land of the silence stretching out between us.” If you can ride with the evolution through frequent wrenching shifts in tone, it’s incredibly poignant. Just because Thomas had no truck with what he considered the indulgent confessional mode of the singer-songwriters of his generation, it doesn’t mean he didn’t speak to the heart. He did, but slant.

Thomas wove these themes and others repeatedly through songs and albums over the years, often reiterating the same lines or place and character names in different songs, a technique he said he’d picked up from listening to old blues. And he would freely salt his verses with quotes from other people’s songs. But he was also steeped in modernist literature. His English professor father was a quasi-beatnik and his mother a painter, the house full of Dos Passos and Ferlinghetti books and Harry Partch and Lenny Bruce albums. His father quoted Walt Whitman so often that it became a pet peeve. Like John Ashbery or Jean-Luc Godard—but also, as he preferred to insist (in an incredible paper he delivered at the 2005 Pop Conference), like the Cleveland-area monster-movie TV host “Ghoulardi”—Thomas’s songs break the frame, invert perspectives, throw around nonsense and non-sequiturs, mix mumbles and howls, combine bombastic high rhetoric with glossolalia and self-deprecating dumb jokes. I think of him as one of my writing teachers.

Though Ubu definitely was one of the links from MC5 and the Stooges to CBGBs to Joy Division, Thomas was irked by efforts to relate what he did to punk, “proto,” “post,” or otherwise. He argued Ubu was elaborating on a lineage that ran back to country and blues through Roy Orbison (his vocal idol) and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins through the Beach Boys’ Smile and the Velvet Underground and Can and Captain Beefheart, a legacy of continuity through reinvention. He wasn’t interested in the pose of “starting from scratch” as self-styled primitives. He started wearing a suit on stage. He adopted the term “avant-garage” instead, with the slogan, “And when they ask you what it means, you just stare at them in disbelief.”

Or at least that’s how he told the story later when punk had become fashionable and “cartoonish.” It’s not like he hadn’t flirted with “year zero” rhetoric himself in the 1970s (see above), and in Ubu songs like “Life Stinks.” The druggie death of Ubu co-founder Peter Laughner in 1977, however, helped reset Thomas against flirtations with social and self- destruction. It might also be what returned him to his parents’ Jehovah Witness faith, to the discomfort of some bandmates.

In any case, the most important “post”-descriptor about Thomas and his compatriots was that they were post-hippie. They graduated from high school into the Manson and Altamont and Watergate years, and while as artsy rebellious kids they were partly products of the counterculture, they also had (intimate) contempt for its naive illusions. If they were going to carry on its bohemian ways, it had to be without its earnest utopianism and other trappings—they would garland themselves with garbage, not with flowers.

They were also proud autodidacts. While they were mostly solidly middle-class, they didn’t look to college campuses for comrades—their rebellion was in not going at all. Thomas had notions of being a microbiologist in high school, but ended up instead as the art director and locally notorious music-and-gossip columnist (as “Crocus Behemoth”) for Cleveland’s Scene alternative paper. As he later told it, he was in the middle of interviewing some touring band whose answers were less interesting than his questions when he thought, “If I’m so smart, why don’t I just do it myself?” It figures that Thomas had a critic’s background. Besides having the cranky-nerd personality for it, what he said about his own work was always a leap ahead of what a critic could come up with, making it impossible not to hear the music through his framework. (And when a critic did have an original insight, Thomas often folded it into his own patter.)

Still, he was given to making cutting remarks about academia and journalism as corrupt, delusional rackets. (“My friend’s a stooge for the media priests,” he once sang.) While I think it was partly to get his professional admirers’ goats, there was a very midwestern chip-on-shoulder in it too. One of my favourite stories I heard about him yesterday was from the musician David Grubbs. On Facebook, he recounted several warm encounters with Thomas, then added: “My one hilarious misstep in killing time with him was, knowing that his father had been an English professor, asking where he had gone to college. Oh, man—that was the wrong question. I remember him staring out the window of the cab and finally saying, ‘I didn't go to college’—unbelievable, hilarious acidity in that spat-out word—‘We were out to take over the world!’”

It’s one of the many ways he made one question everything about one’s own life and choices, which was part of what he was on the planet to do. But he could equally be a source of solace and humour, making you feel like everybody else in the world was crazy and only you and he knew the secret truth. Still, I knew better than to get into a situation where I had to interview him.

I was in university myself when my first close Ubu encounter took place. I must have heard a couple of songs by the mid-late 1980s, including Peter Murphy’s cover of “Final Solution” and some others on Brave New Waves. But the band had been officially broken up for most of my crucial music-discovery years. Then they came to Club Soda in Montreal in the fall of 1988, after the release of reunion/reconfiguration album The Tenement Year. Here’s the video of, as I've written before, my favourite song from that album, “We Have the Technology”:

John Cale was the opening act (!) playing solo on piano, and his version of “Heartbreak Hotel” had already disassembled my brain before Ubu came on and this huge, hilarious, frightening, beautiful man began literally strutting and fretting upon the stage. The music was transcendent. It was the greatest show I’d ever seen at the time, and it’s still way up the list.

(There’s a good 15-minute video of a concert from around that time in Budapest, though I don’t think it quite compares.)

The exuberance of the evening led later that night to the technical end of my virginity, in roughly the same sense that Thomas technically died twice. This all helped bring about the formation of a social circle—still some of my closest friends today—for whom Pere Ubu came to serve as both beacon and codebook. We exchanged confidences in song references, and took road trips to catch their shows when we could. We developed a routine of sending a bottle of cognac backstage for David with a note, and since one of us came from Tehran, he began referring to us as “the Persians from Montreal.” For a short interval we also had our own band and the first thing we learned was “Street Waves” (1977). Here’s Ubu performing it in 2011 in Malmo:

I also saw Thomas stage his elaborate “musical” Mirror Man with Linda Thompson, Syd Straw, and others in 2000 at the Victoriaville new-music festival, and his two revelatory papers at the Pop Conference, delivered with nearly as many tonal and enunciatory loop-de-loops as a Pere Ubu song. Some shows matched the heights of that first one, while others would go off the rails in spectacular fashion, depending on David’s moods. Even the worst wrecks would usually be redeemed by some moment of epiphany. (He admitted he sometimes livened up a flat show by manufacturing a crisis and then bouncing back from it tighter and better than ever, a bit of showbiz sleight of hand—but that invention was definitely born of necessity.)

Unfortunately those chances became rarer and rarer, and now they are over.

Since the pandemic, I’ve been a member of the Ubu Projex Patreon, where he and Kiersty (aka “Ubu Communex”) would do periodic live streams, sharing new music in progress and old performance videos, answering fan questions and bickering endearingly. Boon’s forbearance was impressive, and it was moving how she cherished and took care of him in their relatively recent years together, as well as helping steward his archive and legacy. We owe her a debt. It was also where the increasingly worse news of David’s health would be passed along.

It’s a blessing knowing there’s one more album (I’ve heard some good stuff from it) and more excitingly an “autobiography”—what the hell will that be like?— testimonies to Thomas’s will and work ethic. He’d (adorably) taken up model trains as a hobby in his 60s and said that whenever he considered stopping work, he thought, “What am I gonna do, just watch these trains go round and round the rest of my life?”

But even though I’ve been preparing for it, it’s hard to believe my friends and I will never again gather to witness this man doing what he could do better than anyone, somehow wielding off-the-wall rock songs as levers that bent reality. Even more than when his kindred soul David Lynch fell in January, I don’t want to believe it. I think of these words from “Winter in the Firelands” (on the underrated Worlds in Collision, from 1991):

A road through the firelands, a mark in the snow

That’s where the lonely people bury their hope

Turn back the hands of time

Turn back the kiss of fate

Turn back the eyes of justice

Shoot out the lights and wait

Or perhaps just these lines from “Monster Walks the Winter Lake”:

When I'm gone,

When I'm gone,

Just don't say I never gave you anything

David, no one ever would. I’m raising a brandy tonight. We’ll miss you so much.

One who did was Allen Ravenstine, in this 2010 interview, though again one has to remember that for all his doubtless fair complaints, he played in Ubu on and off for 13 years. And then quit music altogether.

A wonderful tribute to a man like no other. My bandmate Sam played in David’s Australian band and the stories that continue to emerge are always a marvel! I’m glad to hear he had someone that loved him so much and will take care of his legacy and archives.

He was a fascinating guy; one difference with Welles, however, in my opinion, is that ultimately Welles lacked the character and discipline to keep producing work, whereas Thomas just kept pushing forward, kept getting new and great things out into the world. (Of course, film is different than music, in terms of production difficulties, but Welles lived into the age of the indie film and could, I feel certain, have gotten funding and produced new things, even if just based on his legendary status).