Sweeping up kernels from Pop Con 2024

Notes in exile and a vicarious sampler of this year's brainshowers

The annual gathering of music writers (i.e., critics, journalists, academics, musicians, and various disaffiliated thinkers) known as the Pop Conference has been a second home to me for nearly 20 years. It took place the first week of March this year, but I couldn’t be there.

I made my first tentative, anxious trip to what was then the Paul Allen-funded Experience Music Project (EMP) museum in Seattle for the event’s fourth edition in 2005, which was themed around masquerade and personae. Through blogging, I’d just begun making some tentative links to networks of American music writers who’d previously seemed pretty remote. The Canadian border still felt like a real barrier then, and in some ways does today. It was a revelation suddenly to be surrounded by whole roomfuls of like-minded peers, rather than the local sprinkling I was used to. They immediately forced me to think, read, and listen a lot harder.

On day one at that first conference, I heard a roundtable about minstrelsy and blackface that bouleversed my whole perspective on American pop-culture history. A day or two later, one of my personal heroes, David Thomas of avant-rock institution Pere Ubu, performed a lecture on how the whole Cleveland 1970s proto-punk scene was spawned by a manic TV monster-movie host played by Paul Thomas Anderson’s father: “We were the Ghoulardi kids.”

Ghoulardi on Cleveland TV in the mid(?) 1960s. Chuck Schodowski

On a career level, the ties I’ve made at Pop Con have been valuable, for sure. But more so, as the whole field has grown more and more unstable, being able to regroup most years has offered a regular renewal of purpose, a respite from the beleaguered isolation of scrabbling to make a living at a pursuit lots of people consider indefensible or at best redundant. For a few days a year, I get to be with those for whom it’s not up for question whether critical writing is its own art form, one worth fighting and sacrificing for.

To borrow a chorus from Maren Morris, that’s my church.

In recent years, Pop Con itself lost its institutional home at what’s now called MoPop (the Museum of Pop Culture) in Seattle. It went virtual during the pandemic, and now has bounced from the Clive Davis Institute at NYU in Brooklyn last year to the USC Thornton School of Music in L.A. this year—in both cases thanks to Jason King, a Canadian-born musician and thinker whose savvy and hustle are second to none. But along with that displacement, we’ve lost a lot of resources and infrastructural support; the event’s always depended on the kindness of volunteers, but never as much as this.

Meanwhile, the conference has shifted too. It’s far more diverse, thankfully, but unfortunately it’s also grown steadily more dominated by academics, which threatens its unique character. There are ever-fewer professional music writers, as well as semi-pros and autodidact enthusiasts, with the spare time and cash for the trip. And perhaps, under duress, we haven’t done as well as we could at recruiting the next generation. (If you fit that description and are curious, get in touch.)

But yeah, this year I was among those who couldn’t afford the pilgrimage, and I felt it sharply. So I made a search and put out an appeal for posted versions of this year’s presentations, so I could savor some of it vicariously.

The theme this year (currently in academic vogue) was collections and archives, an irony because that’s always been a shaky element of the Pop Conference. (Does anyone remember iTunes U?) Founder Eric Weisbard edited two collections [LATER CORRECTION: three] of papers from the first decade of the conference, but there’s been nothing more like that since. Of course a lot of the work has ended up in peoples’s own books and articles, but we haven’t tracked it, much less built any kind of storehouse for all the one-offs that were purely for Pop Con. I use “we” advisedly, as I was on a volunteer committee with this mandate a few years ago that never got going.

(Partly I got too busy helping Eric start another related project, the online authors’ series Popular Music Books in Process, which started in the pandemic and is still going. You can find that archive on Eric’s YouTube page. In fact we have a session today, Monday March 25 at 5 pm ET, with Darren Mueller discussing his book At the Vanguard of Vinyl: A Cultural History of the Long-Playing Record in Jazz with Nate Sloan of the popular Switched on Pop podcast. Contact Francesca Royster to get the Zoom link and join the mailing list.)

In any case, while I have a chance and a venue, I want to share a few of this year’s nuggets with you today. Full disclosure: All but one of the six posted 2024 presentations I initially found were by white guys, and all from the less-academic end of the spectrum. There’s so much more I wish I could view and share, but [LATER ADDITION, thanks to M. Matos] you can also see the keynote interview with George Clinton (though sadly not the matching panel about the women of Parliament-Funkadelic), as well as the later event with crucial Prince collaborators Wendy and Lisa, where they revealed they’re now working on a project with Annie Lennox, This was the second year in a row a Pop Con keynote made news—last time it was Timbaland dropping the bomb that he lifted the “Are You That Somebody?” beat partly from the Oompa Loompa song. I was so glad to be in the room where that happened.

Meanwhile, please do enjoy the excellent pieces I was able to find.

Robert Christgau, “I Have to Deal with It, It is the Legacy”

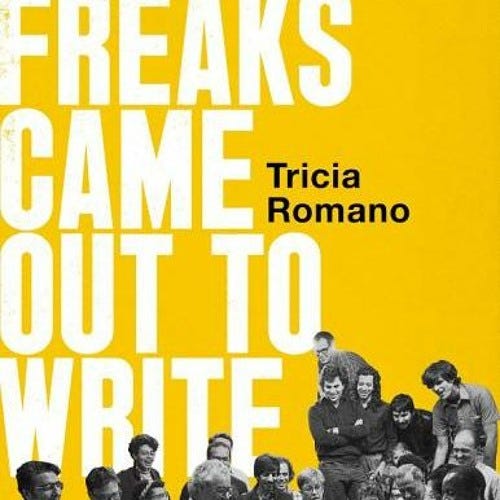

If you read only one of these papers, make it this. Perhaps I was especially receptive because I’ve just finished Tricia Romano’s juicy, engrossing oral history of The Village Voice, her The Freaks Came Out to Write, indispensable if you care about the alternative press, or just journalism, or just culture.

And then here is Xgau, the Voice personified, the deservedly self-appointed Dean of Rock Critics, at age 81, looking at archives and legacy in the disarming light of mortality. Surveying the tens of thousands of albums, CDs, books, tapes, files, and more in his family’s cramped New York apartment, as well as a rented storage space, Bob asks himself, “What the hell are [my heirs] going to do with all this stuff? Will anybody even want it? Because as I assume many of you are still too young to fret about, the answer could well be nope.” His thoughts on the subject are vividly obsessive, in Bob’s distinctive manner, and poignantly emotional in a way all his own too. (It’s a long-running side bet at Pop Con whether Bob will cry during his papers.)

As a bonus, he makes house calls to some of his peers to ask how they are approaching the issue. Those peers just happen to be legends themselves: Voice veterans Richard Goldstein and Vince Aletti, as well as gay liberation pioneer Jim Fourrat, and New York writer/manager/A&R genie Danny Fields.

I find that music on compact disc and less conveniently the resurgent vinyl LP packs a physical authority, or maybe I mean a metaphysical illusion of physical authority, that doesn’t make itself felt so readily when I stream. Although I could be kidding myself, to me it seems as if what I call physicals help me access a frame of mind that informs and to some small but significant extent intensifies my aesthetic acuity and critical commitment, and especially given the old record‑changer trick, where one flat, round, audible object is automatically followed by another that unexpectedly impacts more vividly than its predecessor, usually because I’d forgotten it was up next and found its lead track arresting or the contrast illuminating.

Michaelangelo Matos, “A History of Deep House Page”

Michaelangelo also wasn’t able to make it this year for financial reasons. But it was last-minute, so he sent in his paper as a recording for his panel. Matos is the author of three great books, most recently Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year, but also a 33 1/3 book about Prince’s Sign o’ the Times, and 2016’s The Underground Is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America.

Like several other Pop Con presenters this year, he was inspired by the archive theme to dig into his own files of unused material. Drawing from his dance-music book, he traces how a website that started in the late 90s not only preserved sounds, sights, and memories from the Chicago house scene that otherwise might have been lost, but became a virtual school for producers and DJs yet to come. He’s posted the full text on his own Substack.

And let me point out for younger listeners: This was the Internet, and these people were making connections online—but they were still trading cassettes. In 1999, music was on the precipice of becoming digitized, but it was only beginning to happen. Digital media hadn’t yet really come of age even though digital communications had.

Glenn McDonald, “Talking to Robots About Songs and Memory and Death: Infinite Archives, Fluctuating Access and Flickering Nostalgia at the Dawn of the Age of Streaming Music”

In my recent piece about streaming and “the algorithm” at Bookforum, I wrote about Glenn’s crucial work at Spotify, his layoff near the end of 2023, and his upcoming book. That circumstance lends a bittersweetness to this paper, which he proposed before his firing cut off access to some of the data and materials he was preparing.

He writes, “The problem with externalizing our memories and our note-taking into the cloud isn't technological reliability, it's control. The problem with renting the things you love is not the fragility of the things, it's the morally unregulated fragility of the relationship between you and the corporate angels.”

But Glenn remains a streaming optimist, saying that for all its faults, it must somehow be possible to render near-universal access to a near-complete archive of all recorded music a net positive for humanity.

Individual human obstruction occludes individual archives, but the network of archives, from the well-regulated to the unruly, tends to route around suppression. It's hard to make everybody forget. And meanwhile, my database memory is far, far better than my brain memory. How many of those 13,951 artists could I list without looking? Some. Lots, but not most. But this is how I live, now. How old was my kid when we had the birthday party where their best friend’s brother fell on a brick and had to be taken to the ER? I don’t remember, but I can look through Google Photos and find it by the pictures we took before the panic. Which China Mieville book did I read first? I don’t remember, but I bet I can find the email I wrote you right afterwards. Or maybe I sent it from a work address and so I can’t.

De Angela L. Duff, “Wax ’N Facts: A Musical Odyssey of an Avid Record Collector & Liner Notes Junkie”

Sweet optimism is definitely the main thrust of De Angela’s presentation (on YouTube but also her Substack, “Polished Solid,” linked above), about how a youthful Prince record-collecting obsession blossomed into a life as a DJ, event promoter, podcaster, symposium organizer, and much more.

Her post about her time at the conference also features a gallery of photos and other documentation that really helps give the feel of PopCon, supporting her contention that this year’s was the best (or nearly) she’d ever attended.

My journey into this world began in childhood through my aunt and uncles and since morphed into a lifelong mission to keep Prince's name on the lips of the children. How does collecting physical forms of media and reading liner notes impact individual lives—a journey where every record spun connects us with other music listeners of the past, present, and future, keeping the collective narrative threads enmeshed?

Alfred Soto, “Reissue, Repackage, Reevaluate! The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Hits Compilation”

As well as an excellent critic and teacher, Alfred is one of the last old-school music bloggers standing, or really, a fast gun of a belles-lettres essayist—his “Humanizing the Vacuum” is one of the models I think of when approaching this newsletter. His discussion of Greatest Hits records is a pure pleasure that needs no further exposition from me.

Should our planet survive a series of impending catastrophes, I hope anthropologists will explain the enduring popularity of [the Eagles’] Their Greatest Hits: 1971-1975. By mid-decade the Eagles were undeniable but nothing so far signaled that this comp would spend the ensuing four decades duking it out with Thriller to become the best-selling album in American history, though I’m sure there are weirdos who have pitted “One of these Nights” against “Billie Jean” or “Witchy Woman” against “Beat It.”

Ned Raggett, “The Three Shadows (of the Past): Trying to Tell the Story of Bauhaus”

Ned is a longtime Pop Con stalwart, and an amateur in the best sense—and probably the most sensible way to do this kind of work in 2024—a library professional1 by day but a tireless pursuer of and writer about his cultural passions on his own time.

Here he tells the story of his own adolescent discovery of Bauhaus and the band’s particular way of being at once ubiquitous and elusive, by looking at several recent books that variously scrapbook the foundational goth band’s path through the world.

He also unearths a thick photocopied zine full of press clippings and pictures by some 1980s Bauhausiast who stayed anonymous to avoid the copyright cops, a whole form of fan publishing then that I’d completely forgotten about.

Ned’s posted the text at his Patreon but it’s probably best enjoyed via the video of his charmingly shaggy presentation.

There’s also this remarkable 1981 NME interview talking about a fascinating curio, which resulted from when a member of the original Bauhaus school in Germany, the painter René Halkett, who eventually emigrated to the UK and settled in Cornwall, learned about the band from a young John Peel-listening neighbor, wrote them, and in collaboration with David J released the single ‘Nothing’ backed with ‘Armour.’ It’s the kind of backstory and unexpected surprise that I would never have known about then otherwise, or from the later two collections, so I will always be grateful for this anonymous collection for that reason.

NB: If you’re at all into this kind of thing, follow the links in that quote to the Halkett/David J. tracks—they are radiant artifacts.

I originally called Ned “a librarian,” and he corrected me to say that is not his proper designation. Apologies for the error.

Thanks so much, Carl (which is one of my uncles' name), for including me in this roundup and for taking time out to write about and compile several of the talks from this year's Pop Con! Means a lot! Documentation is so important! I go to great lengths to make sure the Prince symposia I curate are documented. It's wonderful to discover that Eric Weisbard edited three volumes of papers from the 1st decade of Pop Con. FYI. The Clinton link is pointing to Wendy and Lisa. Here's the link to George Clinton's talk: https://youtu.be/PaiBFleJ8Ws?si=61yeGF8oLxvUVFML Thank you, again, and have a wonderful day!