Telling tender spots from funny bones

Between irony and a soft place with Roberta Flack, David Johansen, and Toronto's Cici Arthur

The wonderful new album by Cici Arthur and their release show at the Tranzac in late February got me reflecting on the sonic and emotional space their music occupies, and—with the deaths that same week of Roberta Flack and David Johansen—how attitudes to that niche have changed.

I started seeing Chris A. Cummings play Toronto in the early 2000s under the handle Mantler.1 Usually sharing bills with noisy rock bands and weird experimental projects, he would sit down at an electric piano in a wide-lapeled white suit and frilled shirt (bow tie and carnation were not present but implied), and croon. Sometimes there was a drum machine. Mantler’s quiet, quizzical cabaret tunes were a little bit Broadway-goes-to-Hollywood and a little bit blue-eyed soul—a tipsy minimalist version of what would soon become known as yacht rock. A room-temp cocktail of all things Lite.

While I liked his songs from the first, I also wasn’t sure how to take them. Was this performance art, a lounge-music persona along the lines of Andy Kaufman’s Tony Clifton character or Bill Murray’s Nick the Lounge Singer? Though there was a liberal helping of sardonic self-deprecation—witness “I Guarantee You a Good Time”—Cummings’ stuff wasn’t anywhere near that broadly comic. Still, the outfit and the Mantler bandonym2 signaled a reflexive aesthetic distance, without specifying what kind.

Cummings and I are roughly the same age, and genuine Vegas lounge singers à la Robert Goulet were ubiquitous in the variety-show TV of our childhoods, swiftly followed by the hip parodies of same. That strain of culture was prime fodder for SNL and Canada’s own SCTV when they started, including the likes of Rick Moranis’s Tom Monroe doing current new-wave hits in lounge style. In fact Cummings was once on SCTV as a would-be child actor, in a scene with Martin Short, as he recently related on Instagram and on stage introducing the terrific Cici Arthur song “Cartwheels for Coins,” about being a “showbiz kid.” Knowing of that formative experience on movie and TV soundstages helps me make sense of the combination of sincerity and skepticism in Cummings’ music—the allure of the spotlight undermined by an awareness of its falsehoods, and the embarrassment of still somehow desiring it.

The height of lounge sendups always might be Sid Vicious doing “My Way” in The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle, in which rock’s longstanding contempt for the Lite music it displaced became punk self-hatred. Was Sid (as a vessel for Julien Temple and Malcolm McLaren) making a mockery of Frank Sinatra, or, in a double reverse irony, making a case for his and Tony Bennett’s fading regime of comfortable mastery? This tension persisted through the post-punk generation’s long dalliance with this music.

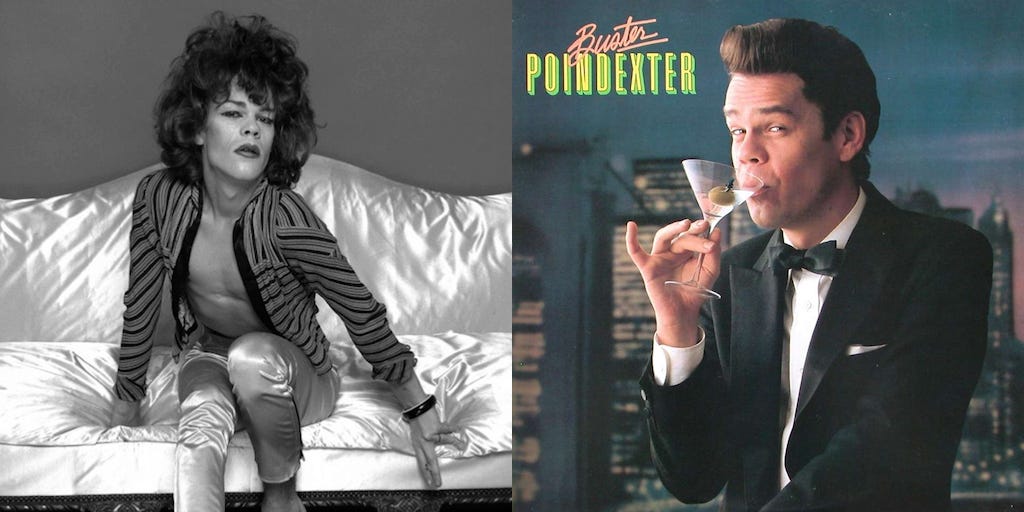

As a kid who straightforwardly enjoyed listening to old swing and jazz records (thanks in part to Joe Jackson’s exciting and heartfelt 1981 Louis Jordan tribute record, as well as my dad’s more casual jazz fandom), I was driven crazy by David Johansen’s popular 1980s Buster Poindexter persona, in ways that presaged my Mantler confusion: Was he just using swing and Latin music as grist for obnoxious narcissistic comedy? Looking back I understand that Johansen’s love for the music was sincere, but the glibness of ’80s hip-to-be-square pop audiences obscured that from view. It all felt untrustworthy. It didn’t help that I wouldn’t really catch up on the New York Dolls for a few years yet, so couldn’t relate one pompadour to the other.

After the news of Johansen’s death, I watched the 2022 Scorsese documentary about him, Personality Crisis: One Night Only, for the first time. Along with erudite interviews and other standard music-doc material, it’s built around an early 2020 set by Johansen at New York’s Café Carlyle, where he performs his own rock repertoire with a lounge-swing combo, i.e., “Poindexter Sings Johansen.” To hear songs like “Temptation to Exist” from the Dolls’ 2009 reunion album with a smooooth band offers a reconciliatory satisfaction. That tune was inspired by the nihilist Romanian philosopher and great existential comedian E.M. Cioran, author of the book Temptation to Exist alongside The Trouble with Being Born and A Short History of Decay. “Someone's always perishing by the self they have assumed,” Johansen sings. “Long after a masquerade, no facade, no costume.” Was he contemplating how the escape initially offered by a clown persona like Poindexter can become a trap?

A psychoanalyst might ask what all these parodies and personae defended against. It was on one hand the smarmy lies of mainstream culture, and on the other what many of us perceived as the failure of the most conspicuous previous attempt to fight back against them, the over-earnest love-generation hippie counterculture. Our irony addiction was born of that disillusionment, and proved hard to shake.

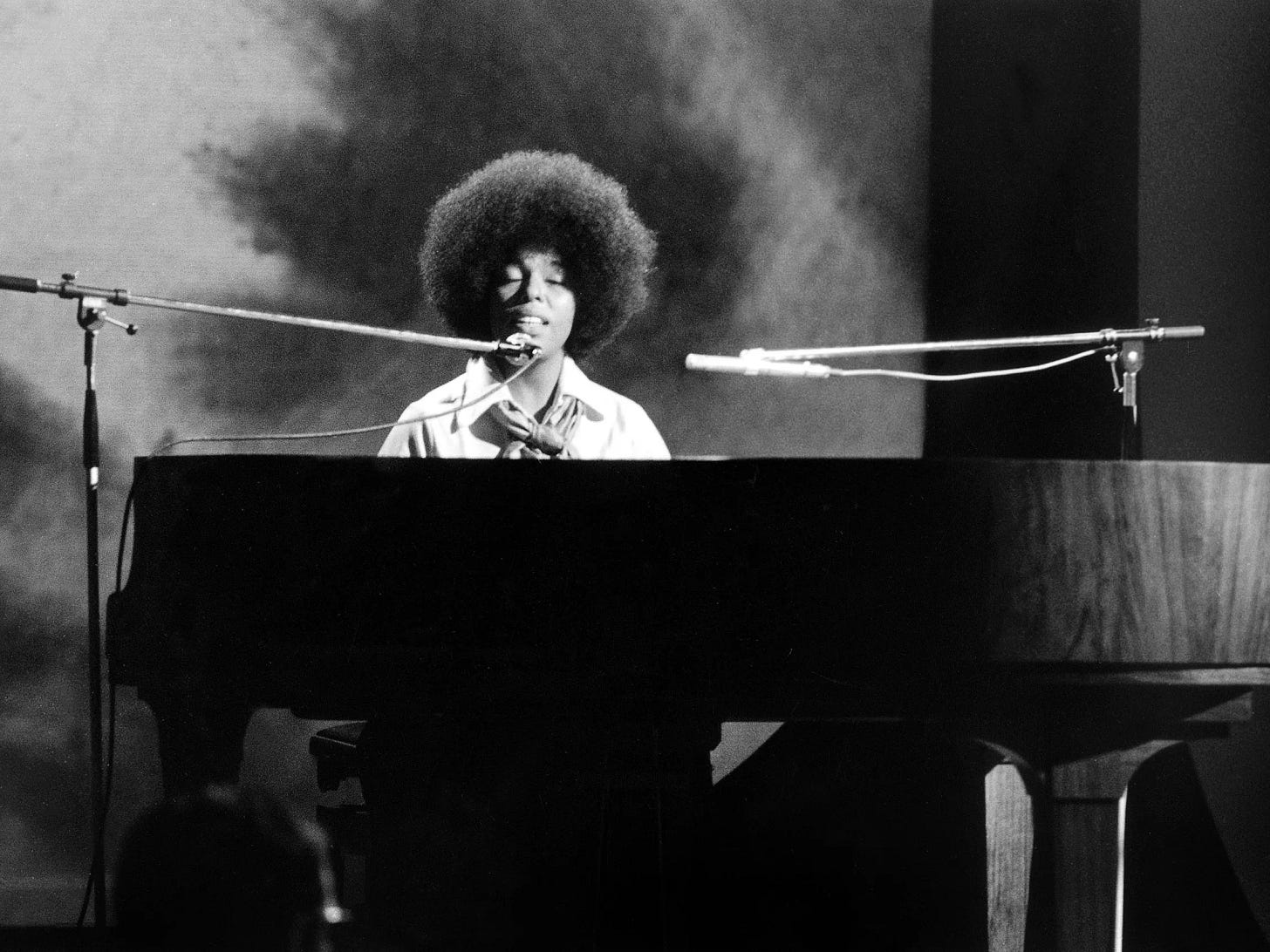

What we less often realized was that we’d inherited that suspicion of softness in part from the counterculture itself, whose militants abjured it if not couched in the approved communal-political or druggy-mystic terms. Roberta Flack’s death prompted a lot of discourse about how the rock-crit establishment was dismissive of her at her peak. Robert Christgau got the brunt, as usual, partly just because he’s chosen to make his whole archive freely available online. But he was far from alone. (Although, as pointed out by Ann Powers—whose magisterial piece on Flack from a few years back is mandatory reading—there were some contrary voices even in the white press at the time, e.g. Stephen Holden and Vince Aletti.)

The way that Flack, Diana Ross, Luther Vandross, Anita Baker, and other “sentimental” Black artists got dismissed as “middle class,” “genteel,” “effete” and unsoulful betrayed a narrow idea of Black “authenticity” that was, yes, racist by implication. But it was also the product of a longstanding leftist idealization of “real,” tough proletarian culture that cut across race. “Sensitive” white California singer-songwriters also were denounced as agents or symptoms of the fall of the so-called rock revolution. (Viz Lester Bangs: “James Taylor Marked for Death.”) These attitudes also derived from male-dominated modernist dogma, that the repressed “truth” artists should liberate would be sexual, violent, dirty, or gritty, more than tender, vulnerable, loving, sad, or afraid.

Regarding “lounge,” a counter-impulse emerged from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s, to rummage below the surface of the supposedly complacent mainstream leisure world and discover the weirdness in plain sight. Partly this was conducted by sample users, who often excavated half-forgotten jazz-fusion sounds by the likes of Roy Ayers (who also died this past week). It was done more pointedly by sound-collageists and “culture jammers” such as Negativland, turning sweet sounds to supposedly subversive ends. And it took place in record collector and zine culture, the milestones being the several volumes of Re/Search’s Incredibly Strange Music books, which helped canonize the “hi-fi” likes of Martin Denny, Les Baxter, Esquerita, and Yma Sumac as “underground” staples.

These waters grew more and more muddied, between love-to-hate appreciation-as-depreciation (or vice versa), genuine cultural-history connoisseurship, and just plain enjoyment. It all came to a head with the neo-lounge/swing “revival” in the later 1990s, which was both the apotheosis and the ruin of this ongoing current. (Slate’s Decoder Ring podcast recently documented the skyrocket and collapse of the trend, though not its longer roots.) The exaggerated bearhug of the shtick drained the fun out of it along with the Cold War radioactive jolt. But the elements still had been disseminated into the popular consciousness, available to be turned to other purposes. Some artists within that radius who had more to offer than retro-ism, for instance Stereolab, or Andrew Bird, retained credibility.

There was also a remnant rebel street cluster of kids who chased the anti-glamourous side of Prohibition-to-Depression culture—hobo train jumpers, string bands, spine-snapping dancers—among which the likes of Hurray for the Riff Raff got their start.

In my first encounters with Mantler, then, I might have wondered whether he was belatedly sending up the lounge-trend bands, or if this squire in his distressed tuxedo was riding out to salvage the music from a field strewn with ripped zoot suits, bent horns, and scattered martini olives. Over time, as “Mantler” became “Marker Starling”3 and a body of work accumulated, I let those questions go, and got used to taking Cummings’ music on its own terms, whatever they might be. I never asked for his own perspective on the presence or absence of irony or satire in his work. Perhaps he’ll offer it in response, or maybe it’s not something anyone can pin down.

One of my favourite Marker Starling songs is “Husbands,” an at once straight-ahead and loopily tongue-in-cheek description of the story of that movie by John Cassavetes, another artist whose degrees of self-interrogation and irony are very much up for debate. This tune by Cummings—whose dayjob for years was at the Toronto film festival—is a delightful example of that all-too-scarce subgenre, “Cultural Criticism, The Musical!”: “I’ve given up on the sublime, and I’m giving the ridiculous a try.”

One of the notable steps forward in Cummings’ later career was to form a touring and sometimes collaborative relationship with Laetitia Sadier from Stereolab. Another link to that space-age-bachelor-pad-culture period, but also an affirmation of Cummings’ place in an echelon that could draw on that material without caricaturing or being consumed by it.

But a funny thing happened in the 2010s: The rockist-modernist attitude that softness is laughable commercialism withered away. (In tandem, not coincidentally, with “selling out,” but it’s not just that.) For me 2011’s Kaputt by Destroyer is a watershed for that shift. I wrote a long essay at the time pulling apart the implications of this outspoken anti-pop subcultural warrior embracing these soft-rock woodwinds and strings—comparing the sound to Minnie Ripperton’s “Loving You,” but Flack would have worked as well.

“It’s not just a change of style but a reassessment of stakes,” I wrote, “as any alteration in an artist’s relation to Beauty has flat-out got to be. After a mid-period of what now looks a bit like a style outliving its agenda, Kaputt transports us to a plane where pre-emptive radical pessimism reconciles with the biological, with the body—which is to say pop music.”

Not all of the thoughts stand up, but more telling is the tone, which gives away how challenging I found this paradigm swerve. (Obviously I’d skipped over the 2000s-emo chapter of the curriculum.) But I was far from the only critic unsure what to think. Today no one would blink at the same sonic palette.

As I’ve previously analyzed at length, the past decade-plus’s embrace of soft sounds and moody tempos has been matched by a younger-millennial and Gen-Z affirmation of maudlin weepiness. This is regarded as feminist and queer self-care, openness about mental health, and emotional common sense among a cohort never scarred by the psychosocial hangups of 20th-century cool.

But never count out the return of the repressed. Or in this case, of the repressive: Authenticity-as-hardness is plenty in evidence in the masculinist-influencer-Jordan Peterson-Tucker Carlson-MAGA-sphere, under the “fuck your feelings” banner. Of course their complaints of victimization and wounded-by-wokeness are a whole other matter.

In that light, no wonder the Cici Arthur record launch was one of the most restorative local gigs in a long while, a collective rallying around the plush, proud velvet flag of, as the album’s last track subtitle puts it, “(So Much Tenderness).” The record finds Cummings with Toronto mainstays Joseph Shabason (sax) and Thom Gill (guitar/keys), with Shabason a veteran of Kaputt-era Destroyer, and Gill a member of Bernice, among many other aggressively non-aggressive projects. For the release party, the trio was augmented by a horn section, a string section led by Owen Pallett, and three backup singers including opener Dorothea Paas—15 musicians in total.

There was something sublimely ridiculous about Cummings’ sad-sackisms boosted into this epic context. I mostly remember smiling hard all night. But a tear or two also might have been shed, for instance over the trio’s encore performance of “We’ve Only Just Begun” by those once-mocked lounge softies the Carpenters. Their reclamation arguably began with Todd Haynes’ film and then an indie tribute album in 1994. But around here it also importantly included a noisy 2003 version of “Close to You” by Pallett and friends’ early, seriously joking band Les Mouches.

Any laughs last month at the Tranzac were in celebration and at no one’s expense.

As Cummings sings in the first lines of the Cici Arthur album’s opening, title track, “Way Through”:

Is this the doorway to a deeper frame of mind?

God knows I need it.

I hear the solemn sorrow of my voice, my kin and kind—

And don’t quite believe it …

Flattering myself to be one of Cummings’ kin and kind, I want to say, yes, it’s okay, you can believe it. After all this time and hesitation, we’ve earned it. Maybe even incurred a duty to protect and defend it—to stand on guard for twee.

A quick note for Toronto-area readers

There already are a lot of updates to my most recent concert calendar, including gigs by the great Mack MacKenzie of Montreal’s Three O’Clock Train in Hamilton and Toronto next week, and a Beverly Glenn-Copeland show with Cici Arthur’s J. Shabason in Hamilton on March 29, among others. Go, look, mark your own calendars.

He was later, stupidly, forced to jettison that name under legal threat from the jazz composer Michael Mantler, which led him to adopt the sobriquet Marker Starling. But that’s another story.

I coined “bandonym” as a term for solo artists who use what sound like group names in my first Pop Conference paper in 2005 (at some point maybe I’ll publish it here). It’s debatable whether Mantler/Marker Starling qualifies, or whether these are more straightforward pseudonyms. But I think it implies the same psychological distancing and disavowal of the then-uncool place of the “confessional” singer-songwriter.

See both of the above notes.

There's a different kind of softness whose implications are more troubling: the sort-of-indie/pop/folk/rock sound we've come to know as Spotify-core. As Liz Pelly wrote about Spotify's reduction of music to background noise for the workday, I expect we're gonna see the return of the appeal of "hardness" (hopefully a version less tied to straight masculinity.)