Tryin' to cure a 40-year ache

Taking solace from survivors of another age of backlash: With Rosanne Cash, Suzanne Vega, and (tonight in Toronto) Mack MacKenzie

The world starts explaining itself more clearly if you live long enough. It does so by repeating itself. What’s striking about the terrible shit going on in the U.S. this year, compared to eight years ago, is how fast U.S. society seems to be reorganizing to conform to the new ideological regime. Universities, art galleries, and newspapers weren’t doing that in 2017; even corporations didn’t just drop their diversity policies. Whether people were “resisting” or not, there was a background assumption that the madness was temporary. Now the madness is how things are. The only question is how far back every power structure will bend to protect itself, or to profit.

And what I keep thinking is, I finally understand the 1980s. I’ve always heard that era of my adolescence described in terms of the Reagan backlash and “greed is good.” Abstractly I get it—I know all the neocon baddies—but because I was just discovering the world then, my experience wasn’t of a radical wrenching shift. Later, yes, with the fall of the Berlin Wall. Yes, with 9/11. Maybe with the sheer relief of Obama’s election. But for alert adults in 1981, as Reagan began busting unions, cranking out nukes, and proclaiming let them eat ketchup, it must have felt similar to what we feel in 2025—that the country had been replaced via rude force with an inverted fantasyland that people were remaking themselves to live in.

Thankfully, for a kid there were so many places to find alternatives; the new music-video channels dropped clues you could follow up at the book and record stores (and libraries, lest we forget), to collect your square pegs and build them into intellectual redoubts. Today, artists like Chappell Roan (and, why not, the recent timely return of her fairy godmonster Lady Gaga, too) make me hopeful da yootz can do the same, despite billionaire-owned quisling platforms shovelling drivel at them and us. Still, it has been a comfort over the past week or so to be able to commune with a few other oddball Eighties holdouts, if only from my seat in the concert stalls.

Rosanne Cash

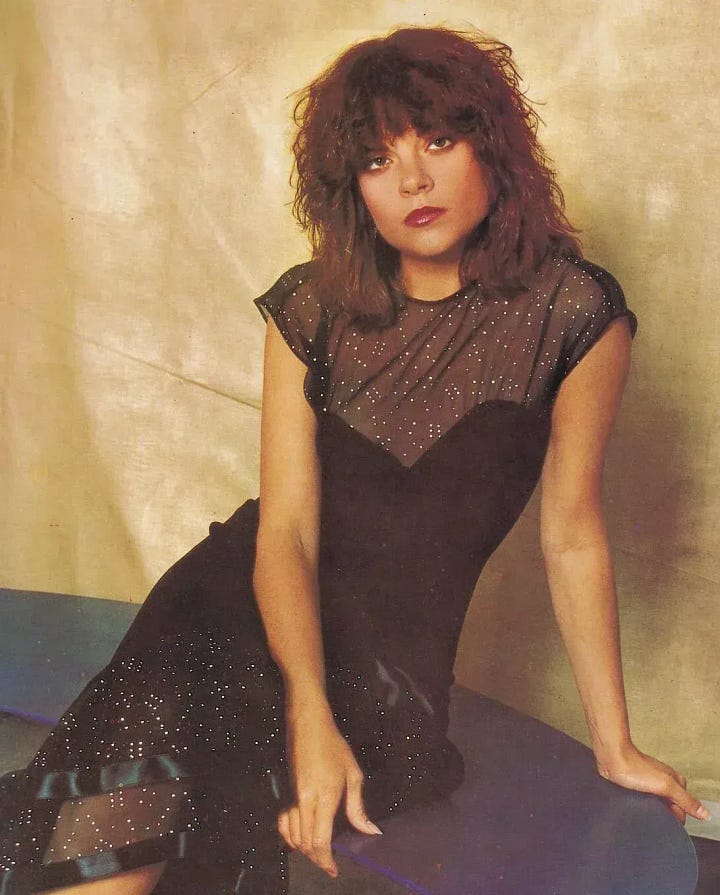

Last Friday, it was a visit to Toronto from Rosanne Cash, that product of country royalty who walked away from the Nashville throne. I was converted to her retinue by my late friend Gordon in the mid-nineties, when he gave me a best-of cassette that was sardonically titled “The Queen of Greenwich Village” on one side—referring to the magisterial singer-songwriter role she settled into in mid-career, and carries on today—and on the other, “The Girl Who Put the Cunt Back in Country” 1—meaning the disobedient Nashville new-wave/rockabilly fashion plate who had hit after hit on the 1980s country charts. I love both sides, but must admit to a special love for the earlier, less-regal rule-bender. She never could have shouldered the historical weight she carries without first playing at shrugging it off.

Cash will be 70 this year (and yes, she looked incredible), and understandably her set list favoured more recent decades—especially as she was accompanied by her husband, producer, and co-writer ever since l993’s The Wheel, the extraordinary guitarist John Leventhal. They leaned especially on 2014’s The River and the Thread, the southern travelogue/genealogy/historical exploration that is her late-career masterpiece. And after all, this was Koerner Hall, that acoustic palace at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory, which doesn’t tend to draw much of a country crowd, though this posher flock lacked for nothing in enthusiasm.

Cash inherited a healthy share of her father’s charisma, then added a variation all her own. There were moments when I’d shiver with unexpected goosebumps merely at the way she delivered a song introduction. But I was particularly touched by her comment after she played 1981’s “Blue Moon with Heartache,” her third country number one. If you know it, you know it’s a heavy weeper. But when she sings it now, Cash said, she doesn’t find it sad, so much as sweet: “It feels almost as if my daughter wrote it.” It’s not always easy to be so generous about the remnants of our younger selves, and that felt like a beautiful perspective to take on the passage of time. If only sadness stayed so pure and simple all our lives as it is when you’re, say, 23.

But no parentheses were necessary when she came to other 1981 track on the set list. While I’m kicking myself that I haven’t seen her live a dozen times before, I can at least exhale with relief that I finally heard Rosanne Cash in person sing “Seven Year Ache” (check out that belt!), a song I had no hesitation putting on my playlist of my 50 favourites ever a few years back. That guitar riff! (Which Leventhal uncannily played simultaneously with the rhythm and bass parts on his acoustic.) Those phrases! (“Face down in a memory but feelin’ all right”; “Heartaches are heroes when their pockets are full”; “There's a fool on every corner when you're tryin’ to get home.”) The sex of it all. (“The girls say, God, I hope he comes back soon.”) Damn, I needed that.

What made Cash and Leventhal sigh with relief, she said, was crossing the Canadian border. Maybe, she suggested, they could stay. At the least, they appreciated getting such a warm welcome as Americans under the circumstances. Don’t worry, Rosie, we know you, and we know who our friends are. As you sang way back in 1990 (but not this week, and that’s okay), “We tried to make ourselves pay for something we've never done. … But what we really need is love.”

Suzanne Vega

It seems like it’s becoming obligatory for touring Americans: Suzanne Vega also opened with an apology at her intimate show at Toronto’s Lula Lounge on Tuesday. (She played another sold-out night on Wednesday.) And likewise, the audience immediately assured her, “Don’t worry, we love you.”

As my friend put it, you have to see Vega live to realize what a theatre kid she is. Literally: She was an English major at Barnard College, as one would have pegged, but she minored in theatre, and had been a dance student at the NYC High School for Performing Arts, the timing perfect to be a character out of Fame. As we learned from another story she told, she was also the dance and folksinging councillor at a girls’ summer camp in the Adirondacks, where she fell for a staffer from the nearby boys’ camp whose opening line was, “Do you like Leonard Cohen?”

Vega’s opening pitch to us was to don a Marlene Dietrich-esque black top hat, atop her black tuxedo-pantsuit, and sing “Marlene on the Wall.” Then she set the hat aside all evening until she popped it back on when the beat kicked in for the DNA version of “Tom’s Diner.” But the sartorial touch I liked best was her chain-link necklace, which ended with a soda-can fliptop at one end and a trapezoid bottle opener at the other, like something you’d have seen someone wearing in their belt loop in the late 80s/early 90s. Flanking her on electric guitar was Irish musician Gerry Leonard, a former David Bowie sideman who like John Leventhal on Friday seemed to summon whole bands’ worth of arrangements out of his two hands, as well as Stephanie Winters on a gorgeous lacquer-brown cello.

Just as Cash spent the 1980s navigating between Nashville commerce and her artier soul, Vega in a way was seeking a similar balance between her literary folkieness (certainly the initial draw when I discovered her first album in high school) and her performer’s attraction to the stylish lures of pop. I don’t know if her coffeehouse friends had the gall to call her a sellout when her child-abuse song “Luka” became an improbable hit (although, as I touched on a couple of weeks ago, not entirely improbably with an “issues” song in 1987). But she wasn’t averse to rolling with opportunities, as the later, far more circuitous journey of “Tom’s Diner” to hitdom illustrates.

Perhaps the commercial zeitgeist of the 1980s is in there. But so is its unpredictable flexibility about what it was willing to market. I think here of the 1986 Philip Glass album Songs from Liquid Days, which featured Vega alongside David Byrne, Laurie Anderson, and Paul Simon putting lyrics to Glass’s music, with vocals by Linda Ronstadt, the Roches and others. It wasn’t pop, of course, but it wasn’t entirely not. It was part of the persistent channel that punk (and music video) had opened up between the mainstream and the art-underground, such that William Burroughs ended up a quasi-celeb on MTV.

Vega swam in that stream like an Olympian. “I had more of an interest in punk than people would know,” she told us in the encore, by way of introducing a post-COVID New York horror-story song called “Rats,” which will be on her new album Flying With Angels, due on May 2, her first in over a decade. “Rats” was influenced, she said, by the Ramones, Dublin’s Fontaines DC, and the Next Door neighbourhood app.

We also learned that the first concert Vega saw on her own, in the late seventies, was Lou Reed, with whom she became friendly in later years. After he died, she said, she was struck at all the Reed memorials that none of the artists paying tribute were playing “the big hit,” meaning “Walk on the Wild Side.” So she decided she would. Of course, the likely reason no one else was doing “Wild Side” was that they didn’t want to do the line, “And the coloured girls sing…” I wondered if Vega might alter it in her version, but she didn’t. Arguably that reflected some lingering downsides of Eighties thinking, though I’m not convinced either way.

I had some related questions about her very theatrical performance of her 2014 song “I Never Wear White,” with its chorus, “My colour is black, black, black… the truth of my situation/ And for those of my station in life.” Which could be seen as a bit much coming from a famous white Barnard graduate. But I don’t mean to overstate—the song is as self-amused as it is self-serious. Its deeper problem is that any anthem about why an artist wears black is going to stand in the long dark shadow of Rosanne’s father’s classic manifesto, “The Man in Black.” It still makes me catch my breath to hear it now.

Ultimately what matters most now about “Luka” and “Tom’s Diner”—though hearing both songs live restored a charge that’s been lost with repetition—might be simply that they’ve allowed Vega to keep making music. What we heard of the upcoming album showed that she hasn’t lost her touch. Given (gesturing frantically) everything, what stuck especially was new track “Speaker’s Corner,” which begins, “I have a newfound sympathy for the madman in the square.” (I chose not to shout out about what Speaker’s Corner means in Toronto, but it still fits.)

The song gets at various angles about the problems of communication and information in the present moment, but it concludes, “The speaker's corner, there it stands/ In politics and song/ I guess we better use it now/ Before we find it gone.” Events this week made those words far more urgent. And that’s territory where we old 1980s and 1990s bohos surely still can be useful, with our principles shaped by Mapplethorpe and other flashpoints of the culture/free-speech wars.

And if you ask me, what are you lookin’ at? I always answer… FREE MAHMOUD KHALIL.

Mack MacKenzie

… And then there are those who never got even one of those career-sustaining hits, but as Gillian Welch sings, are “gonna do it anyway, even if it doesn’t pay.” Tonight I’m (finally!) going to Buy Canadian culturally at the Painted Lady in Toronto, with one of this country’s great overlooked songwriters, Mack MacKenzie of Montreal’s Three O’Clock Train.

That band was a mid-level concern in the city’s 1980s music scene, many layers of visibility below Men Without Hats, alongside the likes of Deja Voodoo or Edmonton transplants Jerry Jerry. As a roots-rock band with a terrific songwriter at its helm in the heyday of Tom Petty and Dwight Yoakam, the Train had more mainstream potential than most. As Montreal Gazette reporter and critic Brendan Kelly wrote in his very welcome recent MacKenzie profile, “When Blue Rodeo was starting out in the mid-‘80s, people would come up to them at shows and say they sounded like Three O’Clock Train, and they did.”

As blessed as Blue Rodeo’s path turned out to be, MacKenzie’s course seemed equally cursed. Some personal demons he’s sung about may have been involved. Attitudes to his part-Mi’kmaq heritage, too; there was no recognized indigenous-music niche in the Canadian scene then. I interviewed him for an Hour cover story in 1996 when his super solo debut was released, with great expectations that again came to little. But to his credit, as Kelly’s piece testifies, MacKenzie’s never quit, or not for long. Whether solo or with Three O’Clock Train, his road case is loaded with 40 years of bangers and heartbusters. I learned about this show only fortuitously from someone on Bluesky after I reposted the Gazette profile. I feel so lucky for the chance to soak up these songs again.

It was actually Rosanne’s stepsister Carlene Carter—the much badder bad girl—who infamously made that crack at a concert in 1979, but in context Gordon’s joke still works for me.

Hey Carl: I've loved Rosanne Cash since the '80s, and enjoy almost all her albums, but I first got hooked on that one-two punch (7-Year Itch, Blue Moon With Heartache). Thanks for the satisfying report.

Rosanne is the greatest.